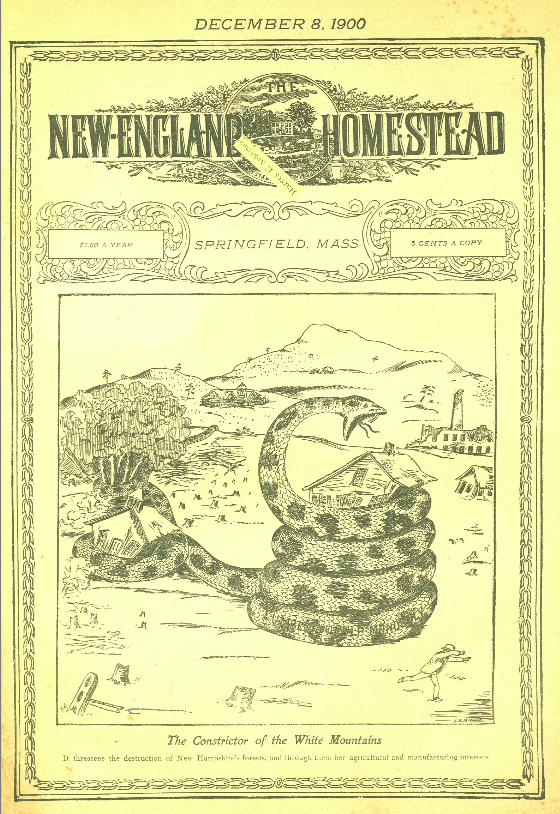

Help for the Hills. The Boa Constrictor of the White Mountains or the Worst “Trust” in the World.

December 7, 2025

An account of the New Hampshire Land Company, a corporation chartered to depopulate and deforest a section of the White Mountains.

By Rev. John E. Johnson (The New England Homestead, December 8, 1900, North Woodstock, N.H.)

What is it? The New Hampshire Land Company.

Where is it? Up among the granite hills of that state.

What is its object? To deforest and depopulate the region lying around the head waters of the Merrimack river in the heart of the White Mountains.

It’s history and modus operandi? In the early days of the company it was allowed to acquire for a song all the public lands thereabouts, and later to “take over” all tax-titles, until finally there were no considerable tracts in that vicinity which it did not own.

It is not necessary to explain the process by which, after a long period of dormancy, the stock of the company passed into the hands of one man for next to nothing.

This was the first stage of the concern’s career.

The next step was also a process of “refrigeration,” and is still going on. It consisted of getting rid of the native population, a hardy stock, who had clung to the home wood lots belonging to the rough areas which they called their farms—for they were more lumbermen than agriculturalists. These must need be driven out to make way for deforesting operations on a large scale.

The method adopted was a very simple one—they were starved out. The company refused to sell them any land. The farmers, exhausting their limited tracts of woodland and unable to buy more at any price, gradually found themselves without logs for their local mills—and almost every farmer had one.1 Their sons, robbed of their winter employment, took no longer to the woods but to the cities, leaving the old folks to fall slowly but surely into the clutches of the company which took their farms from them or their heirs, in most cases for a dollar or two an acre. This process is now going on and may be seen in all its stages from valleys where it has just begun to those out of which the entire population has been driven.2

The land is thus made ready for the professional lumberman who purchases it in tracts of not less than 10,000 acres and begins operations; whose last terms are often written in charcoal. It frequently happens, however, that, owing to misrepresentations as to the amount of timber on them, the denuded tracts fall back, through two or three bankruptcies, into the hands of the company, which thereby succeeds in skinning not only the land but the lumbermen, who are its bitterest enemies.

The last move will doubtless be to get a bill through the state legislature to purchase these deforested areas for a public reservation at a price ten times as great as that originally paid for the lumber lots.

This expelled-native population is displaced for a few years by sturdy French Canadian wood choppers, a number of whom settle down upon any of the old farms that can be captured, and the rest return to the Province of Quebec with their hard earned savings.

In this way the heart of the old granite state is being eaten out, or the blood in its veins displaced with that of a race inimical to the traditions of the first settlers.

Summer visitors to this section of the White Mountains have noticed the many deserted farms and dilapidated buildings and have wondered at such scenes, not dreaming that the cause was to be found in the operations of a company chartered to do it; that this desolation was due to the gradual tightening of the coils of a boa constrictor legalized to crush the human life out of these regions, preparatory to stripping them of their forests; for depopulation here is not due to the causes which have led to the abandonment of farms elsewhere in the state. The inhabitants of this section never depended exclusively upon the scant returns from their rough farms for a living but rather upon their winter’s work in the woods, a dependence that never would have been exhausted had they been left in possession, since their methods were those which are now advocated by scientific forestry. The farmer felled some of the largest trees in the woods every winter and hauling them out endwise injured nothing but rather left the rest the better for it. His successor, the professional lumberman, cuts everything, rolls it down the mountain, crushing the saplings, and not content with that, often burns the refuse for charcoal. The Land Company has boasted that extensive lumber operations never have been undertaken in this section without its assistance in preparing the way—an assistance which in one instance they say involved the preliminary acquisition of sixty different titles.

This White Mountain wilderness is the last considerable one in New Hampshire, the tide of agricultural improvement having long ago surged around it and swept northward leaving untouched, until the Land Company could get in its preliminary work upon it, this grand natural park out of whose heart gushes the Merrimack, which flows the whole length of the state and is the main artery of its economic life. This region is unrivalled for natural beauty this side of the Rockies, and may well be called the Switzerland of America.

The tide of travel to it for health and recreation is an ever increasing one, the governor of New Hampshire in a recent message estimating the annual expenditure of tourists to it at over five million dollars. In view of this fact and the further one that the Merrimack is gradually dwindling, to the great detriment of the manufactories that line its banks, it is amazing that the process of denuding this upper region of its forests in the most wasteful manner has not been arrested, or at least hindered, long ago, and it probably would have been but for the fact that the whole business is largely in the hands of an unscrupulous and merciless corporation—a Trust of the most concentrated, ruthless and soulless character, which is bent on reducing the entire section to a blackened, hideous, howling wilderness.

Nor does the baleful influence of this typical trust stop here. Not content to go its own gait in its unhindered destruction of the forests, it puts its veto on all enterprizes of every description in any region where it happens to be the largest land owner, on the ground that it is the majority, and therefore sovereign. It hinders, for instance, in every possible way the summer boarding house business in which some of the natives have taken refuge. No roads are allowed to be opened through the company’s lands to points of interest, such as waterfalls, lakes, etc., (and it owns in many neighborhoods all but the fringes of the streams and the village sites.) Seekers after health and recreation are repelled and even driven away; deserted farms, with no lumber on them, are “bid up” against sons of the state who seriously accept and would gladly act on the widely circulated advertisements and invitations of public officials at the capital and try to purchase them for summer homes. If the individual competitor succeeds in capturing a mountain eyrie of a few acres and, camping out on it, invites tired out humanity (teachers, preachers, students, artists, et id omne genus) to come and share it with him he can never add to it for love nor money; on the other hand this company does not hesitete to buy a cordon around him, cut him off from the highway and by and by perhaps turn him over to a lumberman who will smoke him out unless he leaves. No physician can hope to purchase a site for a sanitarium from this company, which may partly explain the fact that there is not one in the whole White Mountain region while there are at least six in the mountains of Pennsylvania alone. No hotel keeper, as experience has repeatedly shown, can enlarge his holdings, square a lot, or buy an acre of connecting land, no matter how wild and useless it may be, from this company. The answer is always at last, “We sell only in lots of not less than 10,000 acres and to lumbermen.” Very recently a growing village in the heart of this region, threatened with typhoid fever and the loss of its rapidly increasing summer business, applied to the legislature for a charter for a waterworks which was reasonably sure to pay its way from the beginning but the land company opposed the application by means that can be easily imagined. What chance would a backwood community stand against such a trust before any legislature in the country? The opposition in this case was based on the fact that the company owned all of the real estate in town with the exception of a comparatively few acres and might suffer an increase in its tax rate if the waterworks failed to be self supporting. (The entire cost of the enterprise was $13,000 and the village which already had an opera house and many large hotels was a rapidly growing summer resort.) The only way out of this threatening alternative of death or desertion was at last found in an appeal to the railroad company, whose authority in that section of the state is the only one that is feared or effective and which ordered its attorney to withdraw its cooperation from the Land Company and give it to the town. (The more souls there are in a corporation the less likely it is to be soulless.) The interests of the railroad are permanently identified with those of the regions through which it runs, but this Land Company was organized expressly to ravage and lay waste the sections in which it operates, and is one of the most merciless and unadulterated despotisms imaginable. Its official head often talks about selling a whole town to a pulp company without any allusion whatever to its human population, as though they were so many serfs or slaves and went with the land as a matter of course—like a Southern plantation before the war—or worse still, as though they went with the wood for pulp.

Various individuals and organizations have applied to this corporation from time to time in the name of health, recreation, public interests and individual rights, but in vain. The final answer, after no end of palaver, is always an irrelevant and incomprehensible jumble, in letters, magazine articles and forestry reports (sic) made up of boastings about having facilitated great lumber operations that could never have gotten under way without them, and on the other hand, of never having cut a tree themselves.

The history of this trust furnishes one of the strongest arguments for the Single Tax law that could be adduced. Some trusts have been said to have their public advantages, but this one is an ideal infamy, an unalloyed outrage upon the rights of everybody without one single consideration to recommend it. Is there no way of abolishing or even regulating such a public nuisance? Has any state a right to charter a company to suck its own life out? And what is a state anyway? Is it a corrupt legislature steered by a Land Company which actually exclaims through its executive officer and owner, “I am the state?”

Can there be any wonder that Socialism, Henry George’s land philosophy and the war on Trusts are rapidly coming to the front as political issues? It was such intolerable outrages upon the rights of the people in the name of the law that brought on the French Revolution, and they now threaten to bring on a new American Revolution that will free the bone and sinew of the land from the grinding despotism of Trusts and Corporations. Do the people exist for the laws or the laws for the people?

The “Forest Cantons” are the richest of any of the cantons in Switzerland for the reason that the woodlands there belong to the public; and one will frequently hear how much a town got for wood in a certain year. The “Mir,” or Commune, in Russia holds all unimproved lands in common. Nowhere in the world perhaps, outside of this boasted land of liberty, will you find a population abandoned by its rulers to such a remorseless despotism as this vampire of the White Mountains, the New Hampshire Land Company.

If Trusts and Corporations like this can be legally intrenched under the protection of our Constitution, then the victims of them may exclaim with Madam Roland, “O, Liberty, what crimes are committed in they name!” Life where they are is for the common people a veritable Reign of Terror in the name of Freedom.

The writer of this paper has been for many years a missionary in the White Mountains, under a license from the Episcopal Bishop of New Hampshire, and the statements herein made have been either matters of his own personal experience and observation or have come to him directly from his friends and neighbors, and he will welcome any provocation which will afford him an opportunity to substantiate and supplement them.

What is the use of trying to accomplish anything in any philanthropic or public-spirited way, to say nothing about morality and religion, where the material and political conditions are so appalling? How can you expect people to be honest or virtuous when they are robbed of all collateral means of making a living on their rocky farms and jammed down on to a level of squalor little better than that of their cattle, their forests taken from them and the price of hemlock boards jumped from six or seven dollars a thousand up to seventeen? How can they build cheap boarding houses to save themselves? What wonder that their houses and barns are dilapidated, and their morals also?

Governor Rollins sometime ago called attention to the moral degeneration of many rural regions in the state, but he failed to point out the fact that such degeneration is always associated with poverty and unfavorable physical conditions. What is the use of sending missionaries to communities ground under the heel of such a soulless and degrading Trust as the one in question? The place to evangelize New Hampshire is at Concord. Let the apostles of morality and religion begin at Jerusalem. The most noticible and shameless back-sliding in the state is not to be found, after all, in remote rustic communities but rather at the seat of government. Give the hill towns better laws, more adequate protection for life and property, an exercise of justice worthy of the name. Take the taxes off the summer boarding house business, the last ditch of the lingering native. Take them off the rough farm, the hovel, the one cow, and put them onto the great forests, the only accumulation of unearned wealth in these regions and upon which alone it is possible to “realize” easily and immediately. If the land companies own the towns outright as they claim to, let them pay the taxes on them instead of almost nothing as at present. Require corporations chartered in other states for the purpose of waging a war of extermination of the native population of New Hampshire, to make some report to the authorities of the state in which they operate, and drive them at least out of their attitude of opposition to the efforts of the local government to hold onto its own people—or drive them out of the state entirely. Give the relics of a race which produced a John Stark (the most characteristic American that ever lived) as fair a chance as they would have in Russia (not to mention Switzerland.) Say to the governor of New Hampshire, “What your people want is not more meeting houses but more meat.” They need a Renaissance of domestic architecture and general physical wellbeing more than they need a “Revival” of religion. In the evolution of righteousness political economy precedes piety. The Law goes before the Gospel.

Both political parties have incorporated a plank against Trusts into their platforms for the coming presidential election; will they at least unite in this state in an attempt to crush such an unmitigated outrage upon the rights of humanity as the New Hampshire Land Company.

John E. Johnson—North Woodstock, N. H., July 4th, 1900.

North Woodstock, N. H., June 28th, 1900.

We, the undersigned citizens of the town of Woodstock, do hereby certify that we have read the article on The New Hampshire Land Company written by Rev. J. E. Johnson, and that we believe it to be entirely truthful.

We are furthermore of the opinion that the whole native population of this region will stand by Mr. Johnson in the moderate presentation of the case which he has made at the urgent solicitation of many of our prominent citizens.

F. S. Merrill, Selectman, (Chairman)

Albert W. Sawyer, Ex-Selectman

F. A. Fox, Town Clerk

W. L. E. Hunt, Ex-Town Clerk

Twenty prominent citizens offered to sign the above but it was thought that four were enough for the present. A town meeting can be called later if necessary and the entire population given an opportunity to endorse this article, and take steps to keep the subject before the public.

IN-TEXT NOTES

- It is related that when the news of Bunker Hill was brought to John Stark, he was in the saw mill on his farm, lower down on the Merrimack where he now lies buried. (Has he turned in his grave?)

- Take for a single instance the old Gordon mill up Moosilauke brook just above the Agassiz Basin two miles from the village of North Woodstock. Besides the Gordons there were three or four other farmers that depended upon it. Monroe Gordon built that mill many years ago. It is now for sale for fire wood, or soon will be; the great family of boys scattered from here to the Indian Territory; his and the other farms trembling in the scales of the Land Company—Go up Thornton Gore and see the ruined farm houses and ask for the old mills up there. That beautiful Alpine valley is almost ready for the lumberman. Monroe Gordon was a specimen man of these mountains, of gigantic stature and Herculean strength, as upright morally as he was physically. One quarter of the blood in his veins might have been traced to Passaconaway and the other the other three quarters to John Stark. He fell last winter to the earth and now lies stretched along it like one of the few surviving “first growths” of our fast fading forests. The last boy who has stayed at home “to take care of the old man” may now sell out to the Company and leave for paris unknown. (Could he be blamed if he first carried his father’s bones over the state line into Canada and buried them there?)

NOTES

- Johnson, Rev. John E. “The Boa Constrictor of the White Mountains or the Worst ‘Trust’ in the World.” The New England Homestead, December 8, 1900, 2–11.

- Johnson, Rev. John E. The Boa Constrictor of the White Mountains or the Worst “Trust” in the World. North Woodstock, NH: Self-published, July 4, 1900.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

© 2025 Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society, 501(c)(3) public charity EIN: 22-2694817

Design by The Palm Shop | Customized by Studio Mountainside

Powered by Showit 5

|

Find US ON

Fall 2025/Winter 2026

Visit by Appointment Only:

Please email us at uphsnh@gmail.com

Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society

26 Church Street

PO Box 863

Lincoln, NH 03251

603-745-8159 | uphsnh@gmail.com