Bearding the Old Man—Part Two

December 15, 2025

By Jim Hamilton (Spring 1992, The Resuscitator)

NOTE: If you’d like to start at the beginning, head on over to Bearding the Old Man—Part One

Collecting information about the 1955 bearding of the Old Man of the Mountains led us to David “Stretch” Hays, trailmaster of the AMC trail crew that summer who had mentioned the caper at a winter reunion a few years ago. Nobody had actually written an account of the incident and, since there were hut and trail crew participants involved, why not try to gather the details for publication?

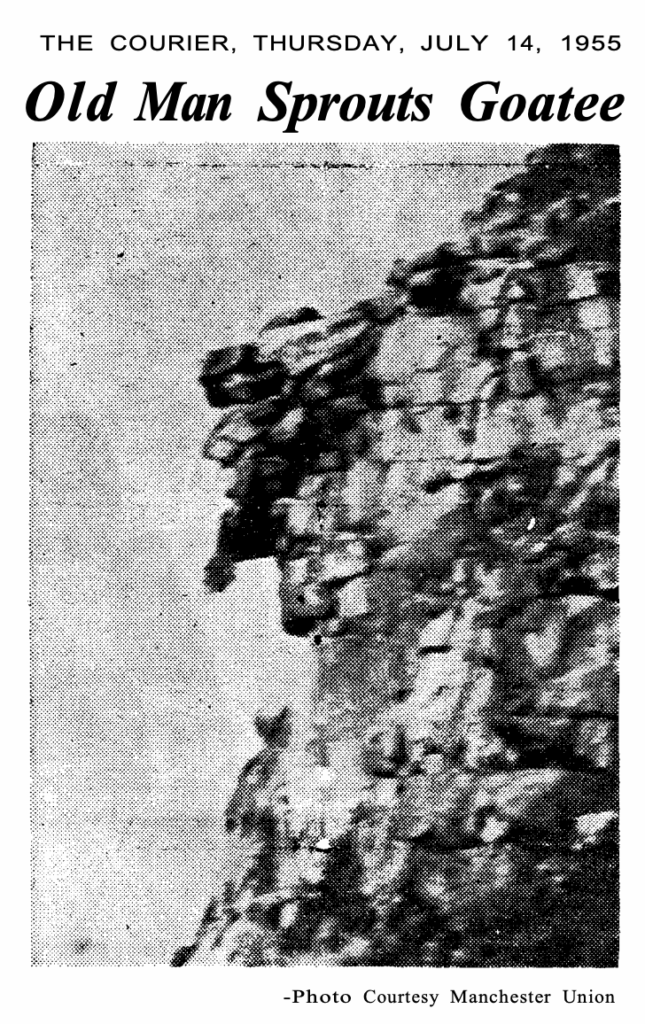

Bill Hoffman, who worked at Pinkham and Zealand from 1949 to 1952, responded to an appeal in the November 1990 The Resuscitator and sent us a glossy copy print from the original photograph that was printed in the Manchester Union Leader and subsequently in the Littleton Courier. Ray Lavender, Jr. supplied us with the Courier clipping which has been reproduced here. What we didn’t expect was the unlocking of the Putnam-Dodge previous bearding caper.

From The Resuscitator, Winter 1990 issue: Special Request for Yarns and Tales—Da Editor specifically requests a copy of the picture published in the Manchester Union Leader in the ’50s showing the “beard” on the Old Man placed by pranksters to give then President Eisenhauer [sic] a good look at the symbol of New Hampshire, hutman style. Slim Hayes entertained a winter reunion with some of the details, but darned if we can remember the whole story, complete with picture. If we can get all the above, you can be sure it will be published in these pages.

Unfortunately, no such photo-documentation was available for the Putnam-Dodge adornment in 1948 which was published in last spring’s The Resuscitator after the secret was shared by the two participants for forty-three years.

Thanks to Stretch Hayes staying in touch with his trail crew cohorts and his membership in the OH (“Old Hutcroo”) Association, he was able to convince several of the 1955 perpetrators to write their accounts of the event for publication here, and was even successful in signing them up as new members of the OH Association. The following summary is from notes sent in from Ray Lavender, Jr., Stretch, Bob Scott, Armistead “Dobie” Jenkins, and Joel Nichols. What a coincidence that three of the hutboys were also sons of prominent OH—Dan and Bob Monahan, sons of Bob “Gramps” Monahan and Ray, Jr., son of Ray Lavender, Sr.

Joel Nichols recalled hearing that Brookie Dodge and his side kick Al “Alfredo Gonzales Freeko” Bolduc, a colorful construction crew member, had attempted the caper, but a frayed climbing rope had caused them to give up. All members of the 1955 contingent agreed that their’s was the first successful attempt. Since both events have now been published in the The Resuscitator, we’ll have to leave it up to the two bearding parties to settle which party should be given proper credit.

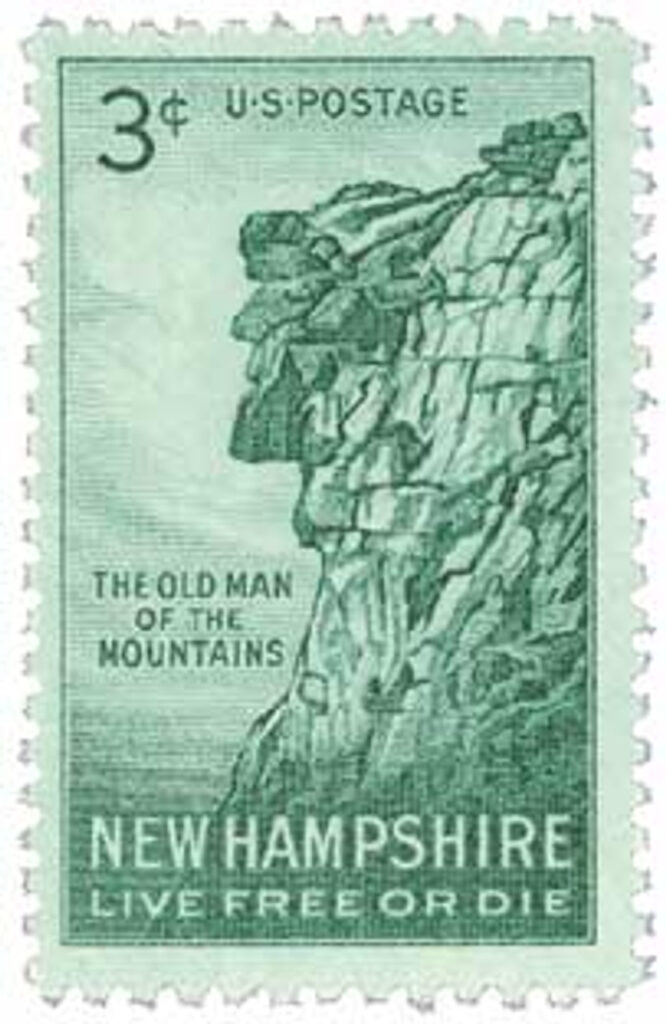

There is some confusion in the memories of the 1955 consortium about the dates regarding the coincidence of the bearding with President Eisenhower’s visit to Profile Lake. Ike was to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the Old Man and also the First Day of Issue of the Old Man of the Mountains commemorative stamp. The celebratory events commenced Tuesday, June 21 and Ike’s visit was scheduled for Friday, June 24 at 9:00 a.m., according to an account published in Frances Ann Johnson Hancock’s book Saving the Great Stone Face (1984, Phoenix Publishing). The hutboy-trail crew bearding happened Thursday, July 7 according to the July 14 Littleton Courier, which was two weeks after Ike’s visit.

Since then, there have been several picture captions attributing the goatee fauna to “enterprising person or persons with more nerves than brains” (July 14 Littleton Courier), “ingenious and daring Dartmouth undergraduates” (Saving the Great Stone Face), or “some prankster” (Appalachia, December 1955).

According to Ray Lavender, Jr. who worked at Greenleaf that summer, it was during an afternoon of swimming and relaxing that the attack was planned on the Old Man. Stretch Hayes credits his three trail crew members as originators of the deed, led by Dobie Jenkins. Joel Nichols remembers that Dobie was a leader, but recognizes that the hutboys also dreamed up the stunt that involved him and Bob Scott. Maybe the idea came about when Scott and Nichols met Gramps Monahan while they were standardizing trails at Lonesome. Gramps was visiting his sons at the hut and may have told the tale of the previous abandoned attempt to beard the Old Man.

Stretch Hayes remembers that he was busy trying to run his trail crew operation and had little interest or experience in attempting a technical rope descent. Scott remembers trying to talk him into it and hearing the excuse that Stretch had a date in Whitefield that night. All Stretch could do was caution his crew to be careful as they piled into Nichols’ father’s Buick Roadmaster for the trip from trail crew quarters at Hutton Lodge in Whitefield to Lafayette Campground.

Nichols remembers that upon arriving at Lonesome, they were disappointed to find goofers, but the Monahans had made arrangements to have the hut covered for breakfast which would be when the pranksters returned from the summit. So the game was on, which included serious planning after supper studying US Geographic Survey maps. Lavender thought that the ascent to the summit was made on a trail called Back Rib (which can’t be found, even in an old White Mountain Guide), Scott remembers it as the Lonesome Lake Trail to the Kinsman Ridge Trail and Nichols recalls climbing through Copper Mine Col and being knocked out for several minutes after hitting his forehead against the ceiling of one of the boulder caverns. In spite of the stop to revive Nichols, the group made it to the Old Man’s forehead a little after 4:30 a.m.

Lavender remembers getting right down to business. “Upon arriving at the scene, we began to cut up small bushes since then there were no large trees. We accumulated scrub brush until there was enough to construct a beard by weaving rope through the beard. Also, the activity had to be done so as not to alert the crew at the summit. That would have been disastrous.” Scott was “a little spooked because we were not sure if there might not be someone left overnight at the top of the tram. As we stumbled down to that little east summit—OH DAMN—it was starting to get light, just a faint pre-dawn gray, but it scared us. We thought we were too late and would be visible from Profile Lake. It was a few minutes before 5:00 a.m. when we got to the edge of the ledges. An early morning pre-sunrise haze covered the low ground. With a sigh of relief, we realized if we couldn’t see down, nobody could see us either.”

The Monahans had the technical climbing experience, though for this trip pack ropes took the place of the more sophisticated climbing ropes and technical hardware of the Putnam-Dodge effort seven years before. Dan Monahan would be the intrepid climber lowered down the face to position the beard. Nichols thought “all this technical rock crap isn’t necessary. So a big loop of rope with the beard tied into it could be lowered with Jenkins motioning down, left, right or whatever.” Nichols returned about four years later to marvel at how successful their efforts had been.

Scott remembered that Lavender had accompanied Jenkins down the slope to get a profile view. “Jenkins had to go almost 1/4 mile down and have his directions relayed up to the Monahans and us. We were all worried that we might not have the right exact place. Which jutting rock was the eyebrow? Which was the nose? Which was the chin? Although the profile is very convincing from below, it was anything but clear up there. We surveyed and made our best guess knowing that if we missed, we would not have time to try again; it was getting light fast. As Dan Monahan belayed himself down, the remaining three of us carefully let out rope, securing it around a tree trunk as he went. When he was in position beside the chin, we lowered down our beard. The trunks were lashed together at the base and the rope we lowered with was tied about the middle of the bundle. Dan wedged the trunk end under the chin and at Jenkin’s directions, we pulled up the beard so it stuck out at the proper, sassy angle and made the upper end fast. As we finished, the sun was beginning to come up; it was about 5:30 a.m.”

Nichols remembers whooping before leaving the forehead, because the first cars in the Notch began stopping. “First one, then another, then another (stopped) as they rounded the curve by Profile Lake.” Descending to Lonesome, the group paused for a well-earned breakfast before hiking down the mountain and riding up to the Lake to see the fruits of their work. Scott said they tried “to look as inconspicuous as possible—impossible of course with those grins on our faces.” Nichols observed “the wind moving it and our cheap pack rope frayed and down she came,” but not before Austin Macauley, a Tramway employee who just happened to have his camera and was on his way to work at the Flume, snapped his immortal picture of the facial fuzz.

Lavender remembers that Gramps Monahan arrived the next day at Lafayette Campground delivering fresh laundry and “thoroughly questioned us about our involvement.” Imagine how embarrassed the New Hampshire State Senator from Hanover would have been if the word leaked that his sons had been involved in the desecration, albeit temporary, of New Hampshire’s granite symbol? Seven years before, Brookie Dodge and Bill Putnam had withstood a grilling by Joe Dodge about their involvement in a similar feat and managed to keep their secret for forty-three years.

There was some apprehension among these 1955 pranksters that the Secret Service men guarding Eisenhower—though he had departed weeks before—and the State of New Hampshire were in an uproar. In a telephone conversation with Joel Nichols last year, Joel thought there had been a warrant issued for their arrest by a Senator Tobey. Most likely, there was a great deal of discussion about the event in the legislators’ chambers in Concord, particularly since the timing coincided with a heightened interest in the Old Man because of the 150th Anniversary. Nobody was named in the warrant, if it actually existed, and the pranksters are safe today. Not that they didn’t have a few misgivings, particularly when members of the Forest Service, whenever within earshot of the trail crew, would dramatically describe how the State was going to prosecute the offenders when they caught them.

NOTES

- Hamilton, Jim. “Bearding the Old Man Part II.” The Resuscitator (OH Association), Spring 1992.

- Macauley, Austin. “Photograph of the Old Man of the Mountain.” Manchester Union Leader, 1955.

- Macauley, Austin. “Old Man Sprouts Goatee.” The Courier, July 14, 1955.

- United States Postal Service. Old Man of the Mountains, 3-cent Commemorative Stamp (green). Issued June 21, 1955.

- United States Postal Service. Old Man of the Mountains, 3-cent Commemorative Stamp (blue). Issued June 21, 1955.

- “Hutton Lodge, Whitefield, NH – 1942.” In “Hutton Lodge,” Trail Crew Association Newsletter, April 2016. Courtesy of Joe May, Trail Supervisor, Trail Crew 1961–1971.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

© 2025 Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society, 501(c)(3) public charity EIN: 22-2694817

Design by The Palm Shop | Customized by Studio Mountainside

Powered by Showit 5

|

Find US ON

Fall 2025/Winter 2026

Visit by Appointment Only:

Please email us at uphsnh@gmail.com

Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society

26 Church Street

PO Box 863

Lincoln, NH 03251

603-745-8159 | uphsnh@gmail.com