The Dodge Clothespin Factory

January 9, 2026

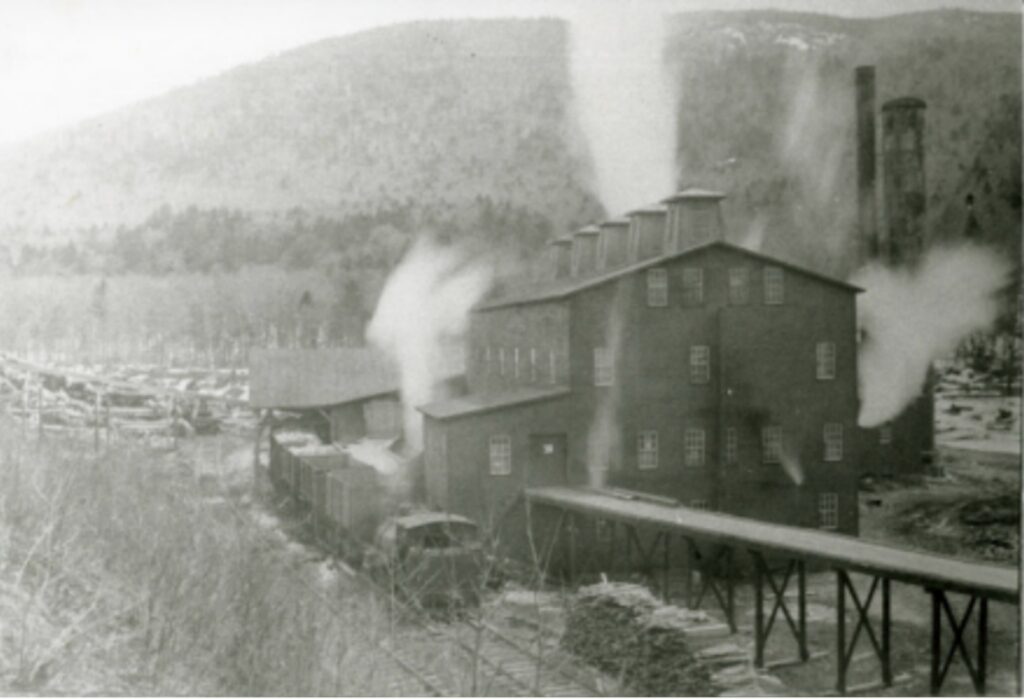

The Dodge Clothespin Factory, Lincoln, New Hampshire

At first glance, a clothespin is almost comically small and mundane: two slender pieces of wood clasped together by a tiny wire spring, a ubiquitous peg dangling from backyard lines across America for generations. Yet at the dawn of the twentieth century, this humble fastener was the fulcrum of an industrial dream — one that briefly reshaped a pocket of Lincoln, New Hampshire.

In 1903, J. E. Henry and Sons negotiated exclusive rights to harvest the rich yields of birch, beech, and maple standing within a two-mile radius of the railroad above Henry’s Dam No. 2. The counterparty was more than a local lumber buyer: it was the Dodge Clothespin Company of Coudersport, Pennsylvania, a firm actively expanding its footprint in the booming wooden goods industry. With iron-horse rails now lifting timber from deep forests, the company aimed to move north, erecting a factory at the eastern fringe of Lincoln’s village near the site of Henry’s first sawmill.

By 1904, the Lincoln Dodge Clothespin Factory was operable, an assemblage of saws, cutting tables, and buzzing machines that promised to convert New Hampshire’s trees into millions of clothespins. By 1906, the operation had grown — a substantial store and a cluster of tenement houses arose alongside the mill, shaping a neighborhood locals would come to call “Clothespin.” It was, briefly, a working-class industrial enclave, a place where timber met tread and the routine of lumbering gave way to something more mechanized.

The Buzz Before the Dryers

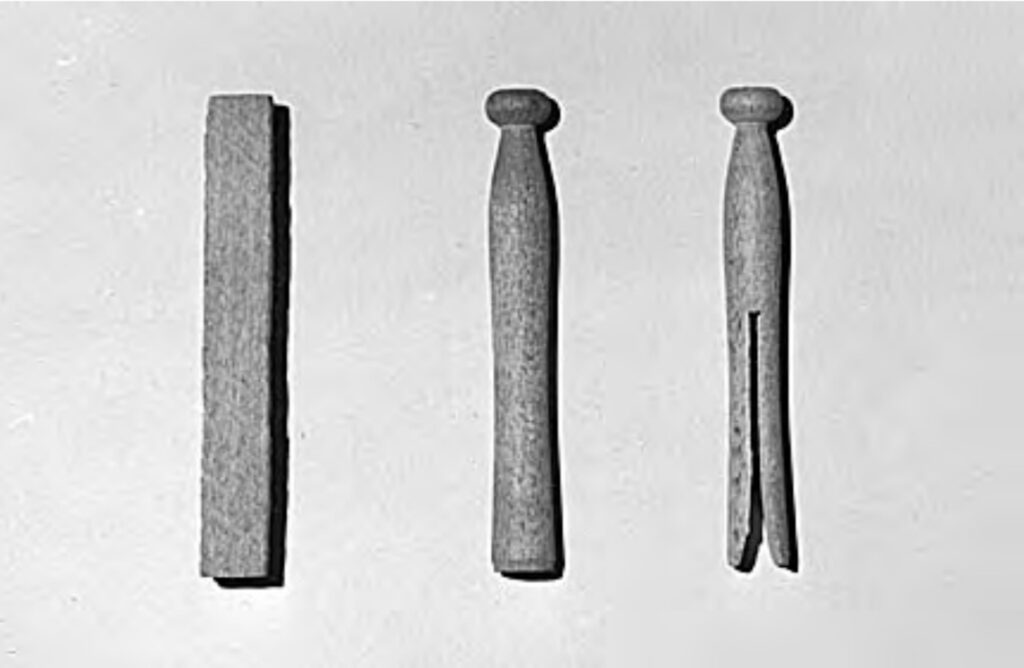

To understand why this unassuming object once inspired factories and communities, it helps to picture its manufacturing process. At its peak, clothespin production was a marvel of rapid motion and precision.

“Steps in Making Clothespins”

“The process of making these is an interesting one. It is done in just six motions. The first one cuts a four-foot chunk off the log, the second saws a board from the chunk, the third saws the board into square strips, the fourth cuts the strips into clothes-pin lengths, the fifth turns the pin, and the sixth cuts the slot into it. This is done very rapidly, and they are then dried and polished in revolving cylinders, after which they are at once boxed and shipped. The capacity is 300 boxes of 720 pins per day, or twenty-nine miles in length.”

This efficient choreography — six operations distilled into near continuous motion — fueled America’s insatiable appetite for clothespins, long before electric dryers or imported plastics reshaped the laundry landscape.

Beyond Lincoln, clothespin production was more than regional. The Dodge Clothespin Company, like several contemporaries in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, capitalized on America’s vast forests and a booming household goods market. Dodge plants helped satisfy demand that stretched across states and into urban centers where lines of laundry swung like banners between tenements.

Eight Years of Pin Making, Then Silence

The Dodge Clothespin Company Dam Trestle, Lincoln, New Hampshire

Yet even as the Lincoln factory hummed, broader industrial forces were already shifting. The clothespin industry — though busy — was inherently tied to wooden lumber and to the rhythms of manual labor. As the twentieth century advanced, innovations in clothes dryers, changing home practices, and shifting market pressures began to undercut traditional wooden clothespin demand. Firms consolidated, competition from plastics and imports emerged, and many small works did not survive the transition.

In Lincoln, the Dodge Clothespin Factory would endure only eight years. By 1912, the site fell quiet, the machines stilled. The houses of “Clothespin” dispersed into memory. Over the decades that followed, the footprint of the factory faded even as its legacy lingered — a small chapter in the arc of regional industry and the town’s ever-evolving relationship with its forests and railroads.

Today, the Nordic Inn occupies the grounds where towering belts of machinery once turned birch and maple into millions of wooden pegs. The inn’s guests may never glimpse the footprints of the Dodge Factory beneath the asphalt and lawn, yet the story remains a quiet testament to Lincoln’s industrial past: that even the simplest objects — a wooden clothespin — can shape a town’s landscape and linger long after the last peg has been packed and shipped.

NOTES

- Castano, David, “Three Hundred and Sixty Million: A History of the Dodge Clothespin Company 1896-1921,” Potter County Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin No. 215, (April 2020): 3.

- “Steps in Making Clothespins,” Lopez, PA: The Icebox of Pennsylvania, “Items of Interest,” http://lopezpa.com/items-of-interest/, accessed on 9 January 2026.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

© 2025 Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society, 501(c)(3) public charity EIN: 22-2694817

Design by The Palm Shop | Customized by Studio Mountainside

Powered by Showit 5

|

Find US ON

Fall 2025/Winter 2026

Visit by Appointment Only:

Please email us at uphsnh@gmail.com

Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society

26 Church Street

PO Box 863

Lincoln, NH 03251

603-745-8159 | uphsnh@gmail.com

Thank you for preserving this history. Reminds me of Livermore Fall

My grandfather , James M Walsh, immigrated from New Brunswick, Canada to Lincoln in1904. His first job was at the Dodge Clothespin Factory. I don’t know how long he worked there or what his position was (he was a carpenter by trade) but he lost parts of his fingers on one hand doing his job. His home remains standing just past the Lodge at Lincoln Station.