A Summer Experience

January 11, 2026

By Howard Kingsbury (The Yale Literary Magazine, November 1861)

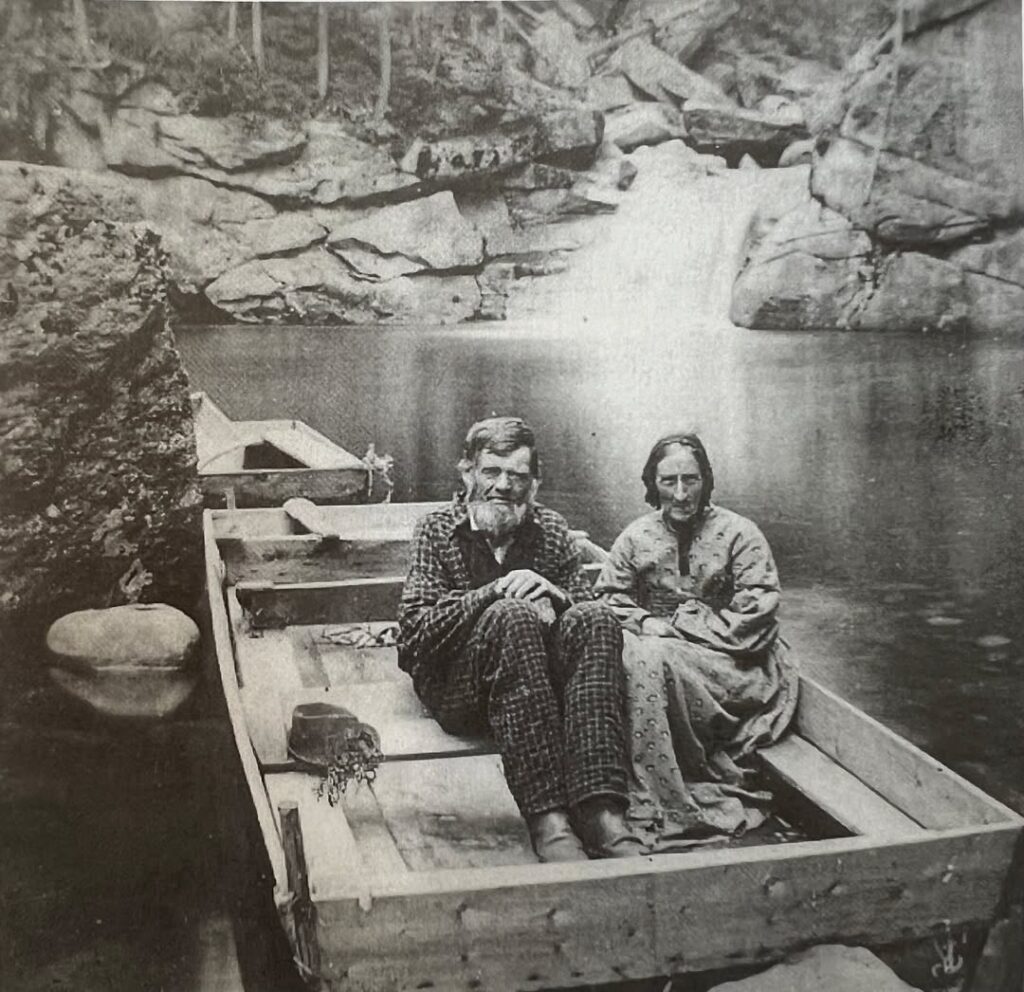

John Merrill and his wife, Rhoda Cilley, in their barge at The Pool, Franconia Notch, NH

Sunday, July 21st, is a day that will long be remembered by all Americans, as the one upon which the advancing army of the Union met the disastrous fortunes of Bull Run. Rumors were rife the following day; by night, a most painful belief had settled upon all, that the Confederates had been victorious, and were almost threatening Washington, while the Federal troops had been routed and cut to pieces. Under such circumstances, and at such a time, the Yale Glee Club began their tour.

We sang Monday evening at Meriden; and although a tolerably good audience was present, the troubled and anxious expressions which were worn, together with the comparatively little enthusiasm manifested, told plainly enough that a deep grief was rankling in every bosom. But additional reports arrived during the night and the next day, revealing a disgraceful and bloody defeat, but not so bad as had been previously represented. News came of the safety of the New Haven companies, lifting a burden from many hearts; and when, on Tuesday evening, we appeared a second time at Music Hall, a second time a large and appreciative audience assembled to hear us, testifying their esteem in a more substantial way than we had a right to anticipate.

On Wednesday, dressed in our White Mountain suit, consisting of blue shirts and pants with white trimmings, and a broad red sash, we left New Haven,—those of us who were not so unfortunate as to be left,—at about noon, for Guilford. There we sang in a church, and after a few serenades, most of our party spent the night in the quiet little Hotel at one corner of the Green. The next morning we visited the Whitefield house, built in 1639—the oldest in the United States—where glasses of beer were furnished us by the matronly cicerone; then down to Sachem’s Head, being cheered on the road as officers of the New York 71st; and afterwards to the cellar where the Regicide Judges, fleeing through town, concealed themselves, and thus evaded their pursuers.

We next went to New London, where we met some graduates of Harvard, engaged in a yachting expedition. After hearing us sing, they crowded around, and said, with generous enthusiasm,—”Well, Harvard has generally managed to whip Yale in boat-races, and we used to have a Glee Club we thought considerable of, but she will have to yield to Yale the palm for singing.” In the afternoon we visited the famous Groton Monument, and stood in Fort Griswold, in the place where Ledyard made his heroic defense. That evening we sang; and the next morning, two, more wide-awake than the rest, paid an early visit to Fort Trumbull, a fort which has only one superior in the land.

Thence, by the morning train, we went to Norwich, visiting here the old residence of the traitor Arnold, wandering under trees planted by his hands, and by the well from which he was accustomed to refresh himself. We were highly pleased with the beauty of the city, which displayed an air of wealth and refinement seldom equaled. We sang that evening, as usual, and hurried on to Springfield the day following. The road between these cities passes through Stafford, a place somewhat noted for its mineral springs. We tasted of the water, the conductor kindly allowing all necessary time. One song on the Depot platform, and then we were off again.

At Springfield we wandered about, until “the shades of evenin’ a comin’ down swift” warned us to appear again upon the stage. The concert being over, we exchanged the stage for a stage-coach, and after a splendid two hours ride, enlivened by stories and song, we arrived in the sleeping town of Westfield. We resumed citizen’s dress on the Sabbath, and attended service. At one church the minister announced that a meeting to be held regularly on Monday evening would be omitted; that he was going to hear the young gentlemen from Yale sing, and he hoped every body else would. According to our custom, we sang in some of the Sunday Schools. The day following, it rained, but providentially cleared off an hour or so before the Concert, and this was the only unpleasant weather we experienced while gone. In the morning, some attended the Examination of the High School, where many men of high position and attainments were assembled, who extended cordial welcomes to our roving College band, and who all remained to hear us in the evening. Our coming from Yale, here, as elsewhere, was sufficient passport to the esteem of many a stranger. With repeated painful partings the next morning, at the Depot, from friends who had largely contributed to the pleasure of many of our number, we were soon whirling rapidly away to Northampton. At the close of the Concert in this last place, an attempt at cheering was mad, which signally failed; but Senator Hopkins, himself a graduate of Dartmouth, immediately rose, and with stentorian voice, cried out, “Three cheers for Yale, and the Class of sixty-three,” which met with a hearty response.

Rising early the next morning, we tramped to Mt. Holyoke. Walking over the quiet meadows in the chill morning air, we, at length, came to the river, and by making good use of a horn suspended from a post, succeeded finally in arousing a veritable Charon. Slowly he came across in his little boat, and by taking two trips, carried safely over our spirits, not as yet disembodied. The ascent was made quite easily, up the 491 stairs to the summit, and then, while we rested our limbs, our eyes feasted on the beautiful prospect below. We examined, with the aid of glasses, the various points of interest; mountains, towns, villages, the ox-bow—and especially the famous South Hadley Seminary. By the kindness of the Proprietor, we enjoyed a gratuitous ride down the Railroad;—we cheered him from below, and he answered with his steam whistle. Then back to Northampton; the coldness of the early morning entirely dissipated by the sun, which beat hot upon our backs, and thence together we retraced our way to Springfield. The editor of the Republican commended us kindly, a second time, speaking of us always as “the boys;”—as gentlemanly in our behavior;—the furthermore, as all good-looking!

From Springfield, we went to Greenfield, where we spent the afternoon in a delightful ride; visiting Deerfield, formerly the scene of a terrible Indian massacre. The old Indian house, as it was called, was torn down a few years since, but its door is preserved, all hacked and battered by tomahawks, and in one place cut entirely through. It gave fearful evidence of the cruelty of that desperate struggle. On the way back, we stopped in front of the Hotel, and taking our place under a flag floating from an elm, sang several of our songs, including, of course, the Star Spangled Banner. The next morning, a part stayed to attend a Sunday-School picnic, while the rest took their departure for Keene. Finally, the others came, and then, for the last time, we appeared upon the stage. It was here that we met the venerable Dr. Barstow, a Congregational minister, who for years had not been known to attend any meeting, religious or otherwise, later than nine o’clock. He did not, however, take his hat and leave at the usual hour, but remained throughout the performance, cheering as well as his age would permit, and congratulating each of us afterwards. After the Concert we were invited to the house of a graduate of Yale, where we met several other graduates, and an exceedingly pleasant and refined circle of ladies.

Saturday morning we met our first sorrow. One of our party was obliged to leave us; so we gathered around him at the Depot, and with the Class Song, and others appropriate, sang our heartfelt goodbyes. Then we followed on our way, arriving in the afternoon in the quiet, antiquated town of McIndoes Falls. We sang, the following Sabbath, in the quaint little Meeting-House, whose only ornament was a center-piece, consisting of two or three rings, inclosing just thirteen stars; and the next morning prepared ourselves for the tramp among the “White Hills.”

We started Monday afternoon for Wells River, riding eight miles in and on a freight-car, attached to a freight-train. At the junction, we took the Littleton road to Littleton, and thence a stage to the Profile House. That thirteen miles we rode free of expense; the hearty stage-driver, who had heard us sing at the Depot, exclaiming, “Godfrey! wouldn’t I carry boys that could sing like that?” While riding, we feasted ourselves with raspberries, which we procured in abundance from children on the road; and, at length, when darkness had begun to descend, covering with a sublime indistinctness the mighty outlines of Lafayette and Cannon, we drew near the Profile House. The evening passed pleasantly with songs, dancing, and conversation, as we began immediately to make the acquaintance of the visitors. The next morning, after playing with the bears,—the usual concomitants of the Mountain Houses,—and watching their comical antics, we walked, by the Old Man of the Mountain, to the Basin and the Flume.

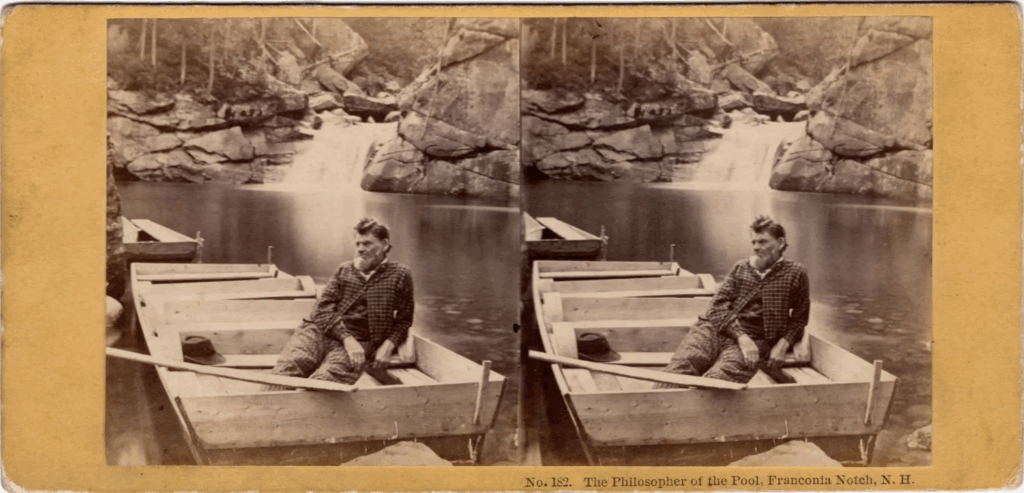

No. 182. The Philosopher of the Pool, Franconia Notch, N. H.

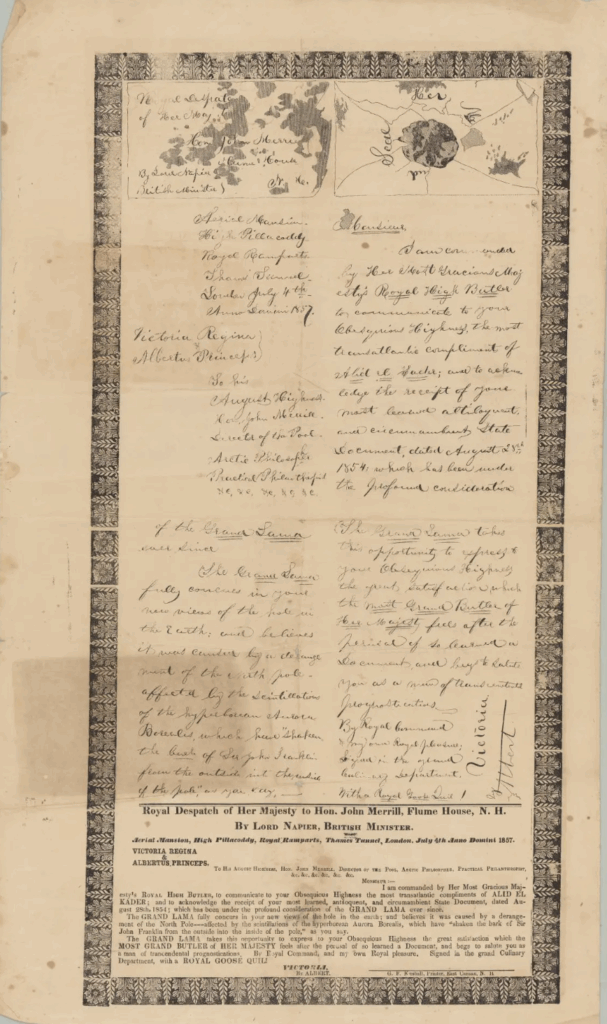

About a mile this side of the Flume, a narrow path to the left brings you, after a half-mile walk, to the Pool. You descend the stone-steps, and suddenly find yourself surrounded on two sides by lofty walls of rock, while over the third pours a beautiful cascade; the spray of which, as you are informed by a sign painted on the rock, is noted for its “heeling” qualities. Here is an old man in a barge, into which you enter, and he paddles you around the narrow circuit of the Pool. When you have reached the side toward the Falls, where the water is from twenty to thirty feet deep, but clear as crystal, he begins to unfold to you his favorite theorty; (for you must know that, is his own estimation at least, the old man is quite a philosopher;) that the earth is a hollow sphere, inhabited on the inside, as well as the outside. He maintains his position by arguments entirely original and irrefutable; has an answer ready for every question, and seeks to proselyte you. He reads a letter he pretends to have received from Queen Victoria, which I here insert.

Note from H. Kingsbury: “Signed in the grand Culinary Department, with a Royal Goose Quill!”

While reading this, or rather repeating it, for he knows it thoroughly, he exhibits an air of self-satisfaction that is really comical to behold. And when he folds it up, and proceeds to explain his charts, he is perfectly irresistible; and with hearty good-will, you wish the ship which Louis Napoleon is to send for him, will soon arrive, that he may have the opportunity of laying his theory, personally, before the savans of France. But we must bid the old philosopher good-by; and instead of going back to the road, we will take this narrow, shady path, formed by timbers felled purposely, leading now by the brook, and now farther back in the woods, through a picturesque route to the Flume. Now we wander about, between the narrow walls of rock, which rise variously to the height of thirty and even fifty feet; in some places covered with moss, and in others bare and damp; and then back, by way of the brook, to the road, and so to the Hotel.

In the afternoon our Club divided; one party visiting Echo Lake, whose echoes they awoke with their songs and shouts, and the Indian’s miniature columbiad; and the other, taking ponies and ascending Lafayette. Those who have taken that ride know what it is, but description would fail to give others any adequate idea. After a long passage through a thick forest, we came to where the trees where of smaller growth, and finally, where they almost entirely disappeared; then to rocks, slanting diagonally, and as smooth as the flagging in the streets, the pony choosing his way as carefully as possible, setting one foot down firmly, and then cautiously gaining another stepping place; then to places where the boulders are laid loosely together, just as in a quarry; and then to flights of stairs. But up and over them the sure-footed beast goes safely as on an ordinary road. Still, one of our party, entranced by the prospect, and failing to perceive a tree which have fallen across the path, suddenly found himself brushed out of the saddle, upon the haunches of his horse; occasioning much merriment to all who witnessed the catastrophe. “The scene,” as Squeers says, “is more easier conceived than described.” With only this accident we gained the summit, and enjoyed the prospect as long as we might, until a cloud settled down upon us with its chilling embrace. The occasional lifting of this veil, produced, with the sunlight, splendid effects, revealing now a distant view down some valley, and now of some mountain; then lighting up Crystal Lake into a single flashing gem amid the darkness, and again whirling around us with its mad fury. But if the ascent was such as I have described it, what shall I say of the descent? Leading our horses along for some distance, we soon mounted, and then over the ridge of one hill and then of another, we wandered, down these stairs, over those jagged rocks, so steep that if you looked straight down, the first object that met your sight was your horse’s ears; then through woods, and finally emerging on the road, we came, Gilpin like, to the Hotel. One word of advice: if you ever visit the Franconia mountains and ascend Lafayette, although others may speak favorably of the gray-horse with the bob-tail, I can warrant the little Canadian pony, and recommend him to you.

In the evening we gave a short musical entertainment, in the Parlor, to the visitors; and the next morning started on. But once more our circle was broken. One poor fellow, just as he was fairly in this Land of Promise, was taken sick, and forced to retrace his steps homeward. Again we formed the ring, and sung and spoke our good byes; and then, with three hearty cheers for the gentlemanly proprietor of that Profile House, who treated us whith almost unparalleled kindness, and three more for the guests, we turned away and directed our course to Crawford’s. It was our intention to walk the whole distance, twenty-seven miles; and by the aid of our staffs, all endured very well for the first nine or ten; but when we arrived at Bethlehem, we found ourselves pretty thoroughly exhausted. Seven, (a friend had joined our party,) less decided and enduring than the others, ingloriously determined to hire a team at that place. Five resolved to finish the journey as they had begun it. One of these five hurried on alone, and arrived early in the afternoon; but the four, taking it more leisurely, stopped for dinner on the road. I can see now the picture we presented after that stoppage. We had waited just long enough to get thoroughly stiffened, and not much rested; and so, with difficulty dragging ourselves from the house, we proceeded on our journey. Hobbling, limping, frantically running, slowly walking, laughing and shouting at each other’s efforts, we finally succeeded in wearing away the excess of rigidity; and after nine miles more, which soon appeared so lengthened out that every foot seemed a rod, we hailed with joy the appearance of the Hotel. Foot-sore and weary as we were, we, nevertheless, at the request of the guests, who had heard of our coming, sang that evening. A good night’s rest removed all fatigue, and in the morning we were ready to proceed on our way. We ascended Mt. Washington in two parties; one starting in the morning, the other at about noon. Those who remained visited Mt. Willard, which commands the finest view of the Saco valley; and the Willey house, memorable for the sad catastrophe to its former inmates. The ascent of Mt. Washington from Crawford’s is tedious and fatiguing. There is scarcely any variety; and it was with feelings of infinite satisfaction, that we entered the Tip-Top house, wearied with nine miles of steady up-hill work. Four hurried on immediately; the remainder spent the night on the summit to witness the sun-rise. The next morning, the cloud which had overhung and enveloped the mountain the afternoon and evening preceding, had settled; and like an even sea covered everything except the highest peaks below us. When the sun rose, it burst through this expanse of clouds, casting shadows off Mt. Washington’s lofty summit on the clouds and mountains far beyond, and then rolling up the mists in gorgeous colors. A few squirrels gain subsistence there; and on that dreary height, springing as it were from the rocks, and nourished by the clouds of heaven, grows a delicate white flower, the only relief to the unbroken wildness of all around.

After a hearty breakfast, we began the descent by way of Tuckerman’s Ravine. We clambered over the rocks and boulders, heaped together in infinite confusion, down the steep mountain side, and across the brook, where a single misstep might cost us our limbs if not our lives, to the head of the Ravine. This Ravine is formed on two sides by wild and lofty mountains covered with dense woods, which slope away to the right and left, and on the third side is shut in by the abrupt declivity we descended. A brook, after finding its way through the rocks and grass, falls over this side, and, by its continuous flowing, forces a passage under the snow, which every winter drifts into this vast amphitheater. Thus is formed the snow-arch, under which you enter, and are surrounded by the snow above and around, while the brook trickles along at your feet. Here we passed a few minutes, snow-balling each other in mid-summer, and then proceeded down the brook. Jumping from rock to rock, supporting ourselves by stunted trees which cover the banks, slipping, falling, our gay suits affording fine contrasts with the dark water, the dun stones, and the sombre bushes, we finally reached a place where a path branched off to the left. Holding a council, for we were without a guide, we determined to enter, and soon found ourselves, in a “forest primeval;” where

“The murmuring pines and the hemlocks,

Bearded with moss, and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight,

Stand like Druids of eld, with voices sad and prophetic,

Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms.”

From the prelude of Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie (1847) by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

There was a kind of sublimity in that forest,—where the only sign of man was the occasional blaze on a tree, and the path we were treading, and whose silence was broken only by our foot-falls and voices,—which was almost oppressive. After about three miles, we came to the new road leading from the Glen House to the summit of Mt. Washington. This road, which was completed and opened only the day previous, will be hailed by many as a vast improvement upon the former tortuous bridle-path. Carriages are now drawn to the very top, and the ascent, heretofore made with so much fatigue and difficulty, can be accomplished without the least weariness. We arrived at the Glen House in safety in the afternoon, meeting two of our advance party, who had been detained by a delay in the transmission of their baggage. At the request of the Proprietor and guests, we who remained sang to a crowded parlor; and the next morning, after a hearty farewell to friends who had been with us at the three hotels, and whose favors had been most generously bestowed, with cheers for the landlord, and waving of handkerchiefs to the girls, till a bend in the road prevented further sight, we rode away to Gorham. Here we separated; most of the party, however, traveling as far as Boston, where our mutual good-byes were finally spoken.

Thus ended our Summer Tour. Three weeks we spent together; during which we saw numerous places of historic interest, especially those in which the heroism and patriotism of our forefathers is embalmed, and many noted for the beauty and grandeur of their natural scenery. On the route, many curious blunders were made; our uniform frequently leading persons to imagine us fit objects for military veneration. Treats we received, almost innumerable, and attentions were paid us; appeals to hurry quickly to Washington were urged; applications for enlistment made; and one old man, who had given a son to the army, ejaculated, in tones we will not soon forget, a fervent “God bless you!”

To speak of the kindness of friends,—of classmates, and college-mates, and graduates; of persons, utter strangers to us, but who received us with open hands and warm hearts, of those to whom a chance meeting has left us under deep obligations;—whose kindness, commencing with our undertaking, continued to its close, and whose substantial favors contributed, more than any other circumstance, to our success and enjoyment, is a task at once the most pleasant and the most difficult. We cannot adequately express our deep appreciation;—to one and all we return our heartiest thanks, and invoke upon their heads the choicest and most plentiful blessings.

As we travel on in life, when cares and troubles perplex and burden us; bright memories of the past will rise to cheer us on, and the brightest of all will be the glorious trip of the Glee Club to the White Watch-towers of the North.

ABOUT JOHN MERRILL

John Merrill (1802–1892) was one of the White Mountains’ most memorable 19th-century characters—a self-styled philosopher, naturalist, and boatman whose presence at the Pool below the Flume became as famous as the landscape itself. Often called “The Man at the Pool,” “The Arctic Professor,” or simply “The Hermit,” Merrill spent more than thirty years guiding visitors through the swirling basin of the Pemigewasset River, offering commentary that ranged from geology and natural history to moral philosophy. He lived for many years in Woodstock, New Hampshire, near Franconia Notch, and frequently worked alongside his wife, Rhoda Cilley. Merrill achieved a degree of notoriety through his self-published 1860 pamphlet Cosmogony; or Thoughts on Philosophy, in which he advanced his own interpretation of the hollow-earth theory. Part showman, part thinker, and part local fixture, Merrill embodied the blend of eccentricity and erudition that fascinated White Mountains tourists and writers alike—leaving an imprint on the cultural history of the region that endured long after his boat no longer circled the Pool.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Howard Kingsbury (1842–1878), a member of Yale’s Class of 1863, was a scholar, musician, clergyman, and gifted writer whose life bridged literature, music, and ministry. Born in New York City and educated at Yale, Kingsbury went on to serve as a private tutor, travel extensively in Europe, and later enter the Union Theological Seminary, where he was ordained in 1869. He held several pastorates before becoming the beloved minister of the First Congregational Church in Amherst, Massachusetts. Kingsbury was also a deeply accomplished musician, playing a formative role in Yale’s early glee club tradition and composing music that remained part of class reunions for decades. In the summer of 1878, shortly before his death, Kingsbury returned to the White Mountains—a place that clearly left an impression on him, as reflected in his earlier essay “A Summer Experience.” That month-long stay, intended as rest and renewal, was among his last. He died later that year at the age of thirty-six, leaving behind a legacy that blends intellectual curiosity, artistic talent, and a quiet but meaningful connection to the landscapes of northern New England.

NOTES

- Kingsbury, Howard. “A Summer Experience.” The Yale Literary Magazine (November 1861): 62–71.

- Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. Evangeline: A Tale of Acadie. Boston: William D. Ticknor & Co., 1847.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

© 2025 Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society, 501(c)(3) public charity EIN: 22-2694817

Design by The Palm Shop | Customized by Studio Mountainside

Powered by Showit 5

|

Find US ON

Fall 2025/Winter 2026

Visit by Appointment Only:

Please email us at uphsnh@gmail.com

Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society

26 Church Street

PO Box 863

Lincoln, NH 03251

603-745-8159 | uphsnh@gmail.com