When the War Came to the White Mountains

January 14, 2026

January 14, 1942—The B-18A Bomber Crash on Mount Waternomee

Douglas B-18 Bolo Bomber

Five Weeks After Pearl Harbor

On January 14, 1942—just five weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor—a Douglas B-18A Bolo bomber carrying a crew of seven airmen crashed into the wooded slopes of Mount Waternomee in North Woodstock, New Hampshire. The impact and subsequent explosions shattered the winter quiet of the Pemigewasset Valley, sending shock waves not only through the local community but through state and federal officials already on edge. The war, long perceived as distant and abstract, had arrived without warning in the White Mountains.

The crash unfolded at a moment when Americans were still struggling to comprehend the speed with which global conflict had redrawn their sense of security. For much of the 1930s, the United States had clung to isolationism, wary of the devastation unfolding overseas after the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939. But by the early 1940s, international events were exerting a gravitational pull that proved impossible to resist. Pearl Harbor marked the decisive rupture. What followed was not only a declaration of war, but a sudden and unsettling awareness that the nation’s borders offered no guaranteed refuge.

The scale of mobilization was swift and unprecedented. By 1941, airplane manufacturing had become the largest industry in the country, with automobile factories converted to produce bombers and other military aircraft. Civilian car production ceased entirely. Even the development of a lightweight reconnaissance vehicle—what would soon be known as the Jeep—became a national priority, with more than a hundred manufacturers competing for a military contract. Industrial America, once geared toward consumer convenience, was repurposed almost overnight for war.

This rapid transformation fed a pervasive anxiety on the home front. Along the East Coast, fears of German air raids intensified. Blackout drills plunged cities into darkness. Ground Observer Corps stations appeared on hilltops and shorelines. Gas masks were distributed, shelters constructed, and citizens trained to scan the skies. At sea, German U-boats prowled the Atlantic, sinking merchant vessels from Maine to the Caribbean and choking off supplies of oil, rubber, and other critical materials. The winter of 1941–42 brought fuel shortages that made the war’s reach tangible in cold homes and rationed hearths.

Daily life adjusted accordingly. Americans collected scrap metal and aluminum, planted victory gardens, and learned to live with ration books that governed everything from gasoline to meat and shoes. Women entered factories and shipyards in vast numbers, their labor promoted through government campaigns that recast patriotism in denim and rolled sleeves. Popular culture followed suit, offering both distraction and resolve: swing music filled dance halls, Hollywood produced films steeped in wartime resolve, and movie stars lent their faces to bond drives and morale campaigns.

It was against this backdrop that the bomber struck Mount Waternomee. For residents of Lincoln and North Woodstock, the sound of an aircraft followed by explosions in the forested hills felt like a sudden breach—proof that the war was no longer something that happened elsewhere. The crash, far from any battlefield or coastline, underscored a new and sobering reality: even the most remote corners of the country were no longer insulated from the consequences of global war. In that sense, the wreckage on Mount Waternomee marked not just a tragic accident, but one of the earliest moments when the Second World War claimed lives on American soil.

A Mountain Meant for Timber, Not War

The bomber came down on the southern face of Mount Waternomee, within what is now the White Mountain National Forest, in a place that had never been meant for habitation. Historically, the mountain’s slopes belonged to timber alone. Settlement in North Woodstock and Lincoln followed the logic of water and access: rivers and streams powered mills, roads hugged valleys, and village life clustered along the Pemigewasset. The higher elevations remained peripheral—too steep, too rugged, too inaccessible for anything but logging. No road climbed Mount Waternomee. The nearest thoroughfare, Sawyer Road—today’s Route 118—ran below, tracing the contours of the land rather than challenging them.

By 1942, the forest on that slope was in a state of uneasy recovery. The hillsides had been heavily cut decades earlier, stripped to feed sawmills and pulp operations, and the woods that greeted the bomber were second growth—birch and hemlock reclaiming ground once cleared. Evidence of the past still lay scattered across the forest floor. The great hurricane of 1938 had left its mark in tangled blowdowns, tree trunks strewn like matchsticks across the slope. When the plane struck, Mount Waternomee was locked in midwinter, its woods deep with snow and its nights defined by subzero cold.

Below the mountain, life followed its winter rhythm. Residents of Lincoln and Woodstock had been reading the headlines—aware that war was no longer theoretical—but that awareness remained distant, filtered through newspapers and radio broadcasts. On the evening of January 14, 1942, most people were indoors, sheltered from the cold. Some gathered socially: Dr. Allan Handy and his wife playing a bridge game at the Lincoln Hotel, Paul Dovholuk visiting among friends, Parker-Young Company workers resting after long days at the local mill. No one anticipated that an aircraft would fall from the sky and pull their quiet towns into the machinery of war.

A Routine Patrol

Even before the United States formally entered the war, neutrality had begun to look more like preparation than restraint. The threat posed by the Axis powers was impossible to ignore, and American industry responded accordingly—factories scaled up production for Allied needs while military planners quietly expanded airfields, training programs, and coastal defenses. After Pearl Harbor, those preparations accelerated into something closer to urgency. German submarines were sinking merchant ships along the Atlantic seaboard, and the United States responded by launching anti-submarine patrols that stretched from New England into the Caribbean, with missions often lasting four to six hours at a time.

To support this expanding aerial network, the Army Air Forces selected Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts—home to Westover Field—as a major northeastern base, while Manchester, New Hampshire’s airfield (later Grenier Field) was developed in parallel. These installations became hubs of a rapidly evolving war effort: bomber training, coastal patrols, and eventually the logistical machinery that would funnel men and aircraft overseas. Units rotated in from the South, bringing with them aircraft that were already edging toward obsolescence—Douglas B-18 Bolos among them—used as interim trainers while newer bombers came online.

The pace was relentless, and improvisation was common. Crews were reassigned, aircraft swapped, and missions flown by men still adjusting to unfamiliar machines. It was in this atmosphere that the B-18A bomber that would later strike Mount Waternomee departed Westover Field at 1:04 p.m. on January 14, 1942, under orders to conduct a routine reconnaissance patrol over the North Atlantic.

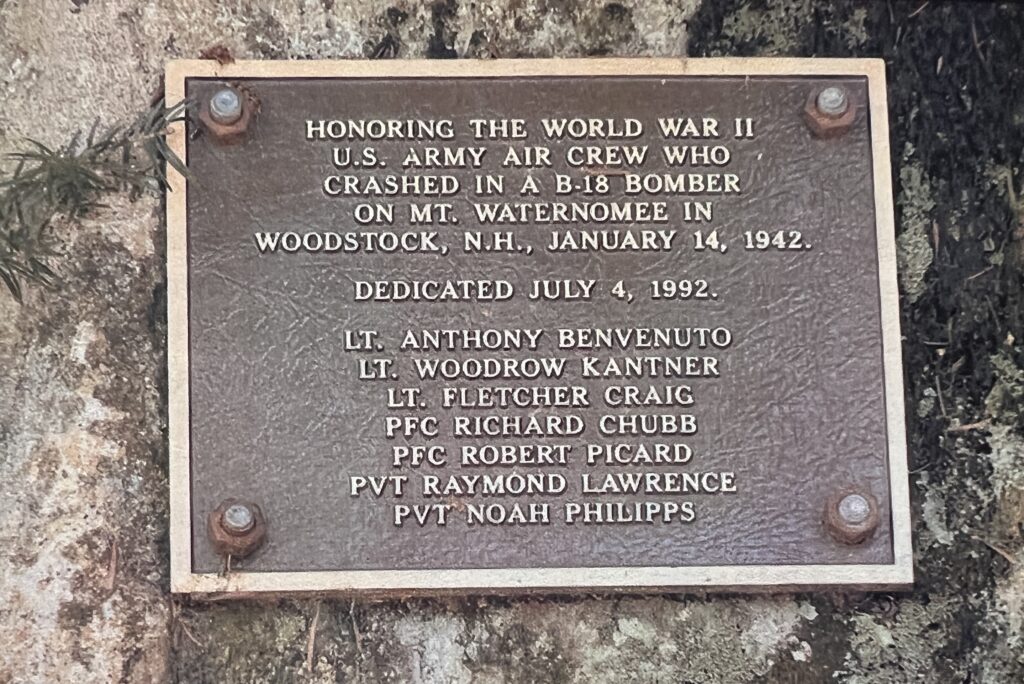

The seven-man crew—1st Lt. Anthony Benvenuto as Pilot, 2nd Lt. Woodrow A. Kantner as Co-Pilot, 2nd Lt. Fletcher M. Craig as Navigator, PFC Richard G. Chubb as Mechanic, both PFC Robert P. Picard and PVT Raymond F. Lawrence as Gunners, and PVT Noah W. Phillips as Bombadier—had not trained together as a unit. Accounts later suggested they were assembled hastily, their experience oriented toward larger, more modern aircraft. But wartime logic prevailed: pilots who could fly one bomber could fly another. At takeoff, the weather appeared manageable—clear skies but strong winds and turbulence. Over land, the aircraft climbed beneath a low ceiling before reaching smoother air offshore, heading southeast some 250 miles out to sea with a favorable tailwind.

The patrol itself proved uneventful. No submarines were spotted. Eager to contribute, the crew lingered longer than planned before turning back at 4:22 p.m., unaware that conditions had shifted dramatically. Winds had veered and intensified, transforming their tailwind into a powerful headwind. Darkness fell quickly. The navigator took a final drift reading before visibility disappeared altogether, rendering the aircraft’s already limited navigational tools nearly useless.

Radio bearings failed amid static. Ground lights were obscured by blackout orders. With no celestial navigation equipment and no illumination in the drift meter, the crew resorted to dead reckoning—estimating position based on time and assumed wind speed. They believed they were making steady progress toward Massachusetts. In reality, they were being pushed backward by winds far stronger than anticipated.

Flying by instruments at 4,000 feet—an altitude chosen to remain below the overcast and above obstacles—the men did what training allowed: they rotated controls, monitored ice buildup, and searched the darkness for signs of land. When they finally glimpsed shore, they climbed and adjusted course, convinced they were south of Boston and closing in on Westover Field. But their calculations were wrong. The headwinds were nearly forty miles per hour stronger than they believed.

Thirty more minutes of flight, intended to carry them home, instead carried them north—across Lake Winnipesaukee, into the interior of New Hampshire, and toward the White Mountains. In total darkness, with no warning lights and no margin for correction, the bomber met the southern slope of Mount Waternomee head-on, bringing a global war—miscalculations, urgency, and all—into a quiet corner of the Granite State.

At 7:40 p.m., the Mountain Appeared

The bomber was flying inland on a heading of 240 degrees, pushing into a strengthening headwind, when the crew believed they had reached the coast. Altitude was increased from roughly 1,600 to 3,000 feet. Conditions were deteriorating rapidly. Snow fell. Ice accumulated along the wings. The cockpit was dark, instruments difficult to read, and the drift meter useless without illumination. Static rendered radio communication unreliable. Navigation had become an exercise in inference rather than precision.

When the aircraft broke through cloud cover, lights appeared below—scattered points in the darkness that offered a fleeting sense of reassurance. The crew believed they were seeing Providence, Rhode Island, which would have placed them safely south of Boston. On that assumption, new coordinates were calculated for the approach back to Westover Field. In reality, the lights were almost certainly those of Concord, New Hampshire. The correction intended to guide them home instead turned the aircraft due north, toward the interior of the state and the rising terrain of the White Mountains.

Until that moment, nothing had suggested danger. There were no visible ridgelines, no warning lights, only blackness beyond the windshield. First Lieutenant Anthony Benvenuto remained at the controls, with Second Lieutenant Woodrow Kantner beside him. The navigator, Fletcher Craig, increasingly uneasy about their position, moved forward in the cockpit but was ordered back. Seconds later, Kantner noticed what he first took to be a bank of dark clouds streaked with white. He switched on the landing light.

It was a mountain.

Kantner shouted a warning. Benvenuto, startled, turned sharply to the right, but the aircraft did not respond quickly enough. Kantner seized the controls, pulling back and forcing the left rudder to bring the bomber level. The plane skidded violently in turbulent air. Benvenuto lost consciousness. The nose lifted, met a downdraft, stalled, and at 7:40 p.m. the B-18A tore through trees and deep snow, slamming into the southern face of Mount Waternomee.

The impact was catastrophic. A tree caught one wing, then the other. Both wings and engines sheared away. The top of the fuselage was ripped open. Wind howled through the wreckage as fuel spilled and ignited. Fire spread quickly along the broken body of the aircraft.

Despite his injuries—a broken arm and ankle—Kantner managed to escape. Richard Chubb, the flight mechanic, helped him move clear of the wreckage. Fletcher Craig emerged shouting a warning that the plane was about to explode. Others followed. Moments later, two explosions tore through the site, hurling debris into the darkness, and into the men. Raymond Lawrence and Noah Phillips, trapped in the rear of the aircraft, were killed.

Contemporary newspaper accounts and photographs confirm the violence of the crash. One image shows a wing standing upright in the snow, impaled like a marker. Others reveal engines torn free and a fuselage left roofless. Physical evidence still on the mountain corroborates these accounts: a crushed wingtip, accordion-folded from impact; cockpit debris scattered hundreds of feet downslope.

Kantner’s split-second intervention almost certainly saved lives. By pulling back on the controls, he prevented the aircraft from plunging nose-first into the mountainside. Investigators later identified a convergence of factors behind the crash—severe weather, icing, low ceilings, unexpected winds, inadequate instrumentation, and the absence of deicing equipment or proper cockpit lighting. The crew had been experienced, capable airmen, improvising under conditions that left little room for error. Under almost any other circumstances, the flight would likely have returned safely to Massachusetts.

Five of the seven men survived to be rescued later that night. In a grim twist of fate, the crash also spared Kantner from a different disaster. He had been scheduled to accompany actress Carole Lombard on a military transport flight to California the following day. That plane crashed shortly after takeoff from Las Vegas on January 16, 1942, killing all 22 souls aboard. On Mount Waternomee, tragedy and survival intersected in ways no one could have foreseen.

Into the Woods After Dark

When residents of Lincoln and Woodstock first heard the explosions echoing through the mountains and saw fire glowing against the winter sky, confusion spread quickly. Some feared that the Moosilauke Summit House was burning. Others wondered—more quietly, more uneasily—whether the war had finally reached their remote corner of New Hampshire.

What followed was a rapid, largely improvised mobilization. Search and rescue teams were drawn from every available source: experienced woodsmen from the Parker-Young Company, U.S. Forest Service rangers, New Hampshire State Police, military personnel, and civilian volunteers. Many headed into terrain they knew well but rarely attempted at night, in winter, through snow two to four feet deep. Snowshoes were essential. Blowdowns blocked passage. Injured airmen would ultimately be lowered from the mountain by toboggan through forest and darkness.

The conditions were unforgiving. Weather reports predicted snow flurries, strong winds, and falling temperatures; overnight lows dropped into the single digits. Survivors of the crash endured the cold alongside rescuers who spent hours climbing and descending Mount Waternomee, cutting trail by lantern light, administering first aid, and building fires to stave off shock and frostbite.

The rescue effort began almost immediately. Dr. Allan Handy changed into ski clothing and packed a medical kit. Sherman Adams telephoned Hans Paschen, manager of the Dartmouth Outing Club Summit Camp on Mount Moosilauke, who in turn alerted the Ravine Camp and the North Woodstock Fire Department. Paschen and John Rand joined Dartmouth students David Sills, Robert White, and Richard Backus, agreeing to meet in North Woodstock as word spread rapidly through both towns.

By 7:45 p.m., the effort was fully underway. Notifications reached Russell Hilliard, the State Director of Aeronautics, who left Laconia for the scene accompanied by pilot Gardner Mills. An Army flash message was recorded. The New Hampshire State Police and U.S. Forest Service were alerted. At 8:15 p.m.—just thirty minutes after the explosions—twelve men entered the woods from the Sawyer Road corridor. Among the first were Neil McInnis, Paul Dovholuk, Robert Kelley, Everett Kinne, and Charles Doherty.

It was Dovholuk, Kinne, and Kelley who first reached the wreckage and the dazed survivors. Cries for help led them to Fletcher Craig, Richard Chubb, Woodrow Kantner, and Anthony Benvenuto. Fires were built to keep the injured men warm. Ralph Goodwin remained with the group while Dovholuk moved downslope to locate Robert Picard, whose left leg had been violently wrapped around a tree.

Soon after, Lincoln Selectman Charles Doherty—a veteran woodsman—and Sherman Adams arrived with a larger Parker-Young crew. They had trail-blazed a path up the mountain and brought toboggans for evacuation. Goodwin headed back down to meet additional rescuers and Dr. Handy, who splinted Picard’s leg at the scene. Kantner, Craig, and Chubb were loaded first and brought down the mountain, reaching the road around 2:00 a.m. Picard and Benvenuto followed hours later, leaving the site near dawn and arriving at the base at 10:00 a.m., six hours later.

Ambulances transported the survivors to Lincoln Hospital. All but Picard—whose condition was too unstable—were later transferred to the Manchester Base Hospital under the direction of Captain Frank R. Fleming and Lieutenant Cahill, in consultation with Dr. Handy and Dr. Betz Copenhaver of North Woodstock.

Once the wounded were removed, the work continued. An Army investigation team led by Major Clayton E. Hughes, Lieutenant Harry Swan, and Lieutenant Howard Schlansker secured the site and searched for the two missing crewmen. With the assistance of local volunteers Joe Mulleavey, Clifford Gagnon, and James Walsh, the remains of Privates Raymond Lawrence and Noah Phillips were recovered and examined by Dr. Leon M. Orton, Grafton County’s medical referee, before being transported to Westover Field in Massachusetts.

Army personnel remained on the mountain through the night and into the following day, recovering sensitive equipment and locating live ordnance buried deep in the snow. One 300-pound bomb required two explosive charges to neutralize. Afterward, officials concluded that nothing of value could—or should—be removed. The terrain was too wild, too remote, and too unforgiving.

With that determination, the B-18A entered another phase of its existence—not as an aircraft, but as an artifact. The wreckage became fixed in the landscape, a testament to wartime urgency, human error, and collective response. Over time, the site would be understood not only as a place of tragedy, but as a quiet record of endurance and community action.

Five men survived the crash: Anthony Benvenuto, Richard Chubb, Fletcher Craig, Woodrow Kantner, and Robert Picard. Their lives diverged—some returning to service, others to civilian professions—but they remained linked by that night on Mount Waternomee. In 1981, survivors returned to New Hampshire for a reunion and a hike to the crash site, accompanied by a New Hampshire Public Television documentary. By then, the bomber had long since settled into the mountain, its story preserved less by wreckage than by memory—and by the people who answered the call when the sky fell into the woods.

What the Mountain Keeps

The mountain itself has changed little since that night. The crash site remains steep and rocky, thick with mixed hardwoods and softwoods that form a dense canopy overhead. Boulders punctuate the slope, and fragments of wreckage—muted now by time, moss, and leaf litter—still lie scattered among them. From certain points, the land falls away toward the Pemigewasset River, offering a view that feels expansive and indifferent. Wildlife moves freely through the trees: deer and moose, bear and birds, the only regular inhabitants of a place briefly and violently interrupted by human tragedy.

Today, the site is recognized as a protected archaeological resource within the White Mountain National Forest. It is not marked by directional signage, nor reached by any maintained or publicly listed trail. Finding it requires effort, navigation, and intention—an approach that mirrors the way the mountain itself has always resisted easy access. The absence of a formal path is not an oversight, but a form of stewardship. It ensures that the site remains quiet, undisturbed, and intact.

Nothing may be removed. No metal fragments, no remnants of machinery, no small pieces carried away as souvenirs. What remains belongs where it fell—part of the landscape now, and part of the historical record. The scattered debris is not debris at all, but evidence: of wartime urgency, of miscalculation and endurance, of the men who flew and those who climbed through snow and darkness to bring survivors home.

In choosing to leave the wreckage where it lies, the mountain keeps its memory honestly. It does not monumentalize the event. Instead, it holds the story quietly, beneath trees that have grown taller since 1942, beneath snow that returns each winter, beneath a sky no longer darkened by blackout orders. For those who seek it out, the site offers not spectacle, but reflection—a reminder that history is not always preserved in museums or monuments, but sometimes in remote places where the forest closes in and the past is allowed, finally, to rest.

NOTES

- Bunker, Victoria, Sheila Charles, Dennis Howe, and Russell White. B-18A Bomber Crash Site Historical Research and Field Documentation. Report prepared for the White Mountain National Forest in partnership with the Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society (NEAT-06-079; AF-1484-P-06-0155). December 2006.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

© 2025 Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society, 501(c)(3) public charity EIN: 22-2694817

Design by The Palm Shop | Customized by Studio Mountainside

Powered by Showit 5

|

Find US ON

Fall 2025/Winter 2026

Visit by Appointment Only:

Please email us at uphsnh@gmail.com

Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society

26 Church Street

PO Box 863

Lincoln, NH 03251

603-745-8159 | uphsnh@gmail.com

The local communities did what small towns did, springing into action to help in any way possible. I have heard the stories many times from my dad and others and it seems impossible that anyone could survive such a crash and explosions. To me that site will always be hallowed ground.

Hallowed ground, indeed! Any particular stories shared by your dad that you remember well? Perhaps a favorite you’re willing to share?