Bearding the Old Man—Part One

November 27, 2025

By William Lowell Putnam (Spring 1991, The Resuscitator)

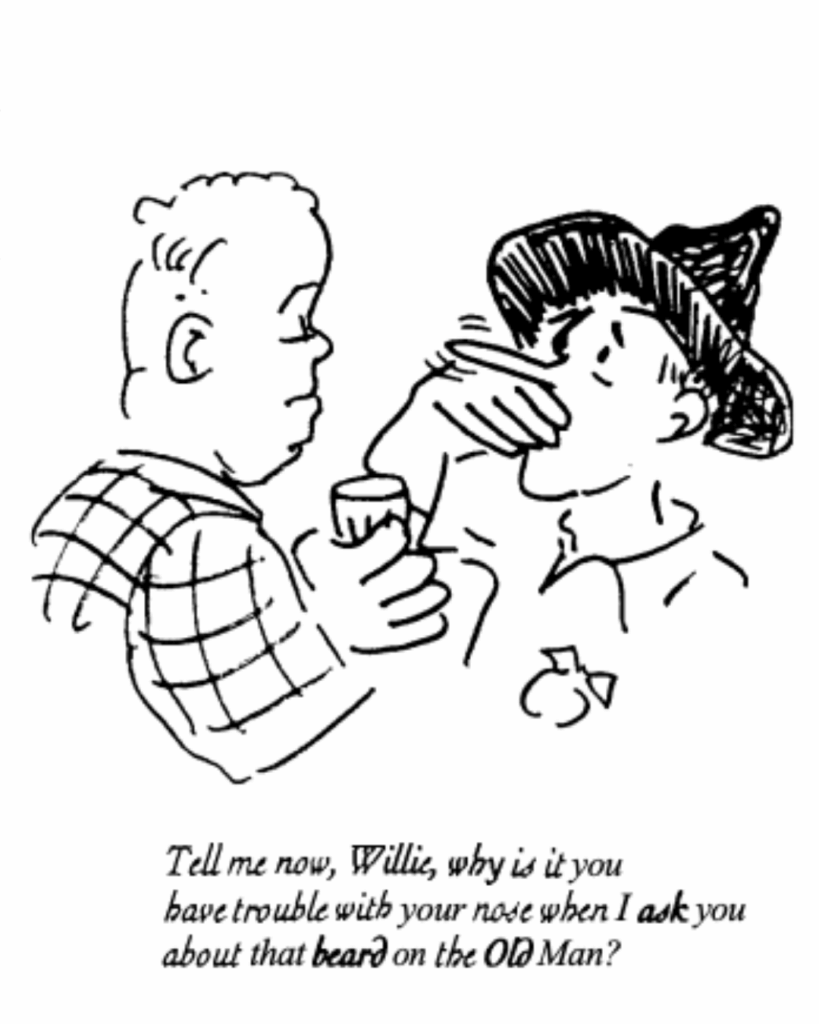

Little is known about the first attempt to beard the Old Man of the Mountain because there are no known photographs or newspaper reports to document the event and the principal players included the celebrated son of the other “Old Man”—Joe Dodge—who would not have taken kindly to knowing that son Brookie “Hirum” went AWOL from Lakes of the Clouds to pull off the daring stunt. It’s interesting that the secret was so well kept that, years later, a second bearding party knew that Hirum and an accomplice had attempted to attach a tree to the Old Man’s chin, but were probably unsuccessful. After all, if a tree falls in a forest with nobody around to hear it, does it actually make a sound? -da Editor

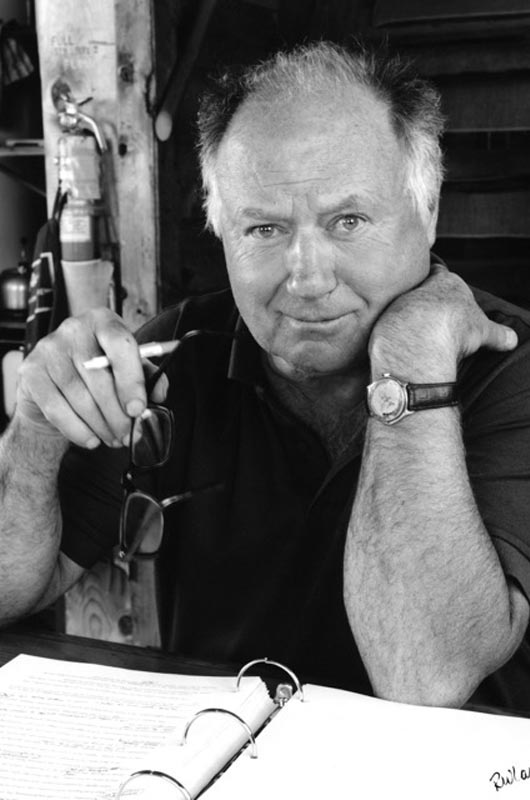

William “Willie” Lowell Putnam

Joe Dodge

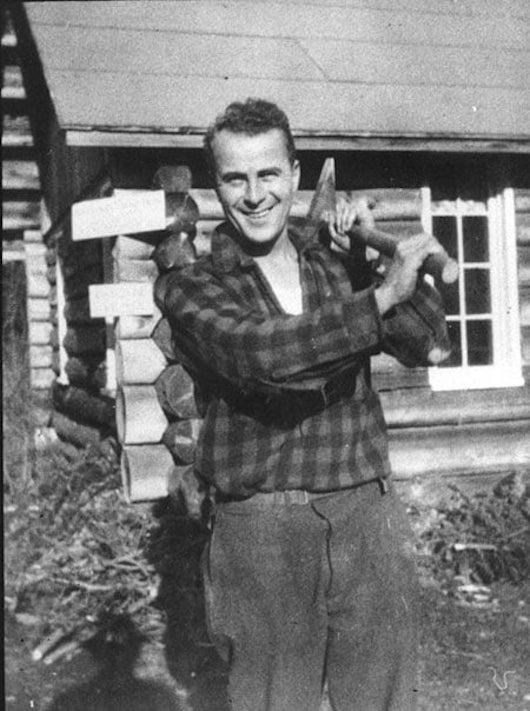

Joseph “Hirum” Brooks Dodge Jr.

In the early summer of 1948, the old man asked me to join Bob Temple as opening crew of the Western Division. Since my car was a convertible and the Pinkham truck was busy hauling stuff up the summit, I was able to negotiate top dollar for my services—$10 per week. The last hut to be opened was the easiest of access—Lonesome, where Temple left me to fend off the goofers for a few days in the company with Shorty Lang. There must have been a truly perverse streak in Joe Dodge the day he assigned Shorty to the place.

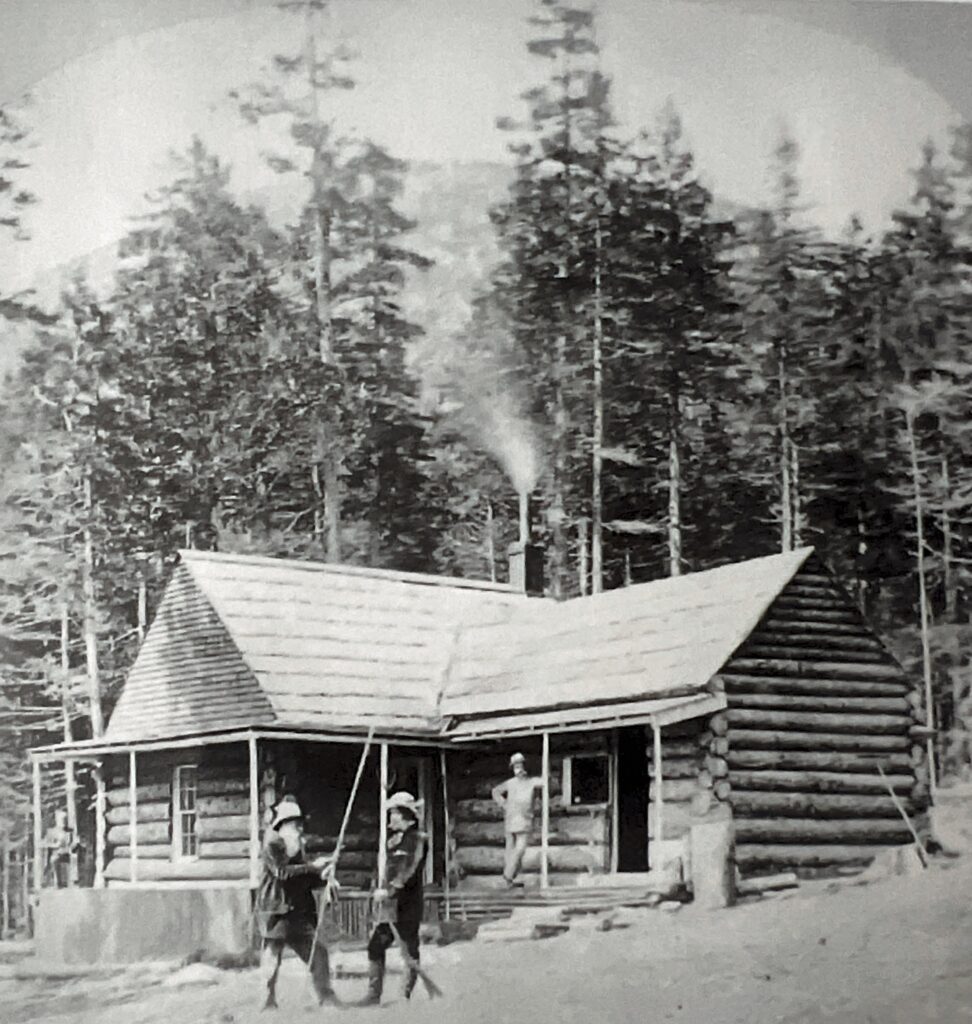

The original Lonesome Lake hut actually belonged to the State of New Hampshire and had been a log cabin fishing lodge owned by Dr. William Prime and his buddy the newspaperman, “Droch” Bridges. The doctor’s sister, Annie Slosson, wrote a bunch of North Country stories, including one about Fishin’ Jimmy. I point this out only to indicate the antiquity of the structure for the benefit of those who never saw the dump. Those of us who did, however, had firsthand knowledge. Joe Dodge, for instance, had solved the problem of its rotting substructure by ignoring it, and the whole place was compressing into the ground. Thus, the beams supporting the second floor (such as it was) were now only six feet above the main level. I could straighten my full height only when standing between them; Shorty was unable to stand erect anywhere.

Lonesome Lake – an 1876 Fishing Camp Built by Author W.C. Prime

I mention this problem … our obvious solution was to spend as much time outside as possible, possibly go for a climb on the nearby Cannon Cliff, which we were planning to do had not the most horrendous rainstorm in recent history struck the White Mountains during our stay. The result was that we had to stay inside, where the frequent impacts with the overhead probably affected our judgement.

In any case, when the rains finally stopped, we found that landslides had come down all over the place, blocking the highway through Franconia Notch and partially filling Profile Lake. When Joe Dodge was finally able to send in the regular crew, Shorty and I went down to see the mess. We also looked up on the cliff and again contemplated a climb, but I had a date to go climbing in British Columbia and now had to head West in a hurry.

Later that summer, I returned to Pinkham Notch, checking in with Joe Dodge to see if he had anything gainful for me to work on. The old man allowed as I might as well head up to Lakes and hammer on a few shingles and maybe smear some concrete around the foundation. I’d find his son up there someplace, he said, and Hirum would know where I could be most useful. So I drove around the mountain to the Cog Base Station where I’d have somewhat quicker access to my car than at Pinkham and hippedy-hopped up the Ammonoosuc to the Lakes.

Lakes of the Clouds Hut, courtesy of Corey David Photography

Hirum sure had a pile of shingles to affix to the place—all around the sides and roof of the new addition. At this point, I can’t remember which of the umpteen additions to Lakes this was, about midway along, third or fourth, I guess.

We hammered away for a few days, until the job was mostly done. Hirum appeared to be very much in demand; the hutmaster was apparently some guy named George Hamilton, but he was alleged to be down off the mountain with appendicitis, and Hirum was doing a lot of the cooking as well as straw-bossing the construction.

After a few days, word came up on the moccasin telegraph that the old man wanted me to go over to Evans Notch as soon as the shingling job was finished at Lakes. It seemed that the couple he had running that place had to clear out for something better and Joe needed a replacement crew for the last two weeks of the season. He must have been getting pretty close to the bottom of the barrel.

Later that day as the two of us were banging away on the wall, Hirum had asked me if I’d have time to show him a bit about rock-climbing before I left for Evans Notch. I thought about the fine cliff on which I had enjoyed climbing and which Shorty and I had contemplated earlier that summer.

“Cannon’s the best cliff in New England, Hirum. Want to go over there on days off?”

“Christ, Willie, my old doesn’t plan to ever give me a day off.”

“Hell, Hirum, he’s not going to miss you for one day. We can go down to my car and get over there in less than two hours.”

Hirum’s conscience was too strong, or else his fear of parental retribution, but not his desire for a little extracurricular excitement.

“I just can’t take off all day, Willie; the old man’ll kill me. But, would it be possible to get over there some night and maybe put a beard on the other Old Man?”

“What are you gettin’ at, Hirum?”

“Hell, Willie, you’ve been all over that part of the cliff. You must know how to find the rocks that make up the stone face.”

“Oh sure,” I replied, reaching for another handful of shingles, “there’s a nice variation on the Old Route that goes right beside it.”

“Yeah, but can we do it in the dark?”

“Well, I don’t think the cliff itself would be so bad in the dark, but I sure don’t want to go stumbling around on the talus below. That’s miserable enough in the daylight.” But I still hadn’t grasped his full intent.

“C’mon, Willie, I’m not after you to climb the Christless cliff; what about just hanging a beard?”

“You mean you only want to hang some kind of tree on the chin?”

“That’s it; you’re not so slow after all.”

“In that case,” I thought for a moment while reaching for more nails, “it shouldn’t take very long ’cause there’s an easy pathway alongside the edge of the cliff—all the way to the forehead. We use it for the descent route all the time.”

Old Man of the Mountain on April 26, 2003, Seven Days Before the Collapse

So it was that I went over a few points on belaying methods with Hirum before we adjourned after supper that very evening and managed to find our way to the top of the Old Man’s forehead just as the daylight was fading. Rather than show our silhouettes against the darkening skyline, we went some distance back of the cliff to fetch a suitable black spruce. It measured about fifteen feet and was all we could negotiate through the scrub to the edge of the cliff.

Having climbed past the chin area before, I knew where there was a good crack that would hold a loosely inserted piton, but still be well out of reach for anyone except a fairly confident climber. We knew that once the “beard” was discovered, the State Park people would hustle over from the tramway and chop it free, and we didn’t want this to be any easier than it had to be.

Tying an ancient and reject climbing rope around its butt—a leftover from my activities in Canada—we eased the tree over the edge at the inside comer where my pleasant route crested. Gently we lowered until it hung freely from twenty-five feet—about halfway down the chin. In a lowering mode, Hirum was able to handle its weight alone. Anchoring him to one of the giant turnbuckles on the summit, where his belay would be bombproof, I climbed down the crack to the “beard.”

I knew there was a good piton already in place down there someplace, but finding it in the dark was difficult. As it turned out, the pin was covered by the tree and I had to struggle it out of the way before I was able to secure myself with a ten-foot tether and release Hirum from his belaying chore.

My next task was to negotiate the tree far enough out from the comer so that when it was lowered the rest of the way, it would be properly seen on the Old Man’s chin and not back against his Adam’s apple. I got Hirum to lower it a few feet more.

There was a dinky, little ledge out along which I could move while pushing the stump end of the tree, until I felt it was nearly the proper distance out from the main cliff. Then I slid my piton into place and put a Prusik knot on the ancient rope—it was to remain with the beard.

“O.K., Hirum, lower the tree.” I called up through the still night air.

Soon it commenced to slide slowly down, as I eased the moving rope through the Prusik knot.

“Not too fast, Hirum. We’ve got to stop it just right.” I looked downward in the dim light, hoping to see well enough to stop the lowering process in time.

“That’s it, Hirum!” Two more inches and hold it there.” I allowed the Prusik knot to tighten and then bent down to assure myself the beard was properly positioned.

“O.K., Hirum, it’s secure. You may drop the rope.”

In a matter of seconds, the lowering line was whizzing past me into the darkness below, coming up sharply onto my piton. I coiled up the slack and tied it off at the piton, not trusting the Prusik knot to last forever. Then I slithered back along the crack into the corner where Hirum’s belay would once again be meaningful, and I could climb easily back up to his stance.

We were in our sacks at the Lakes shortly after midnight for a few hours sleep; Hirum had arranged with some others of the crew to get breakfast going.

Later that morning, as I was placing the final few shingles on the east side of the new wing, Hirum cam outside and beckoned me away from the others working near the wall. “The old man was just on the pipe; they’re pretty pissed off over at Cannon.”

“What old man?”

“My old man, you jerk.”

“What did you tell him?”

“I said I didn’t know anything; I was dishwashing last night and had to get breakfast ready for eighty goofers this morning. I couldn’t have anything to do with whatever they’re pissed off about.”

“Think he was convinced?”

“Maybe.”

“Did he ask about anyone else?”

“Nope, and I didn’t volunteer anything.”

Hirum and I finished off our remaining summer duties without further comment from his father on the matter of the beard. But, simply by keeping our ears open, we learned that the Franconia Park potentate was pretty put out because his men couldn’t get down to our piton to cut the tree away, and the beard stayed in place for several days until finally the wind swayed the beard back and forth enough to fray the rope through.

I never thought further about the whole business until about five years later when I was sipping some classy Scotch with Joe one evening and soaking up a lot more or less truthful information about some early doings in the White Mountains. After an hour or so, Joe abruptly changed the subject asking me about a beard that I might just have been a party to hanging on the Old Man’s chin a few years earlier.

It seemed that the State Park people had called Joe around mid-morning the day after we had done our deed. The manager had sent a couple of men over to “shave” the Great Stone Face, but they’d come back unsuccessful. They’d been able to see that the tree was tied off to a piton “driven” (that was the dirty word used) into the rock where only a skilled climber could have gotten. Some members of Joe’s extended family were the obvious suspects, and there had been an extended discussion on the matter. There was also some question raised about defacing the State property, for which the penalties are unknown and enormous. Joe, as was his typical manner in handling this kind of employee problem, had stone walled the punitive complaint, and when the “beard” had finally dropped off, the issue was dropped, too.

I took another sip of the Scotch and asked Joe what he knew about the Statute of Limitations for offenses of this nature. He didn’t seem to have a lot to say on this fine point of the law, but leered knowingly at me before our conversation turned to other topics.

William Lowell Putnam has held numerous offices in a number of mountaineering clubs and is also editor of several climbing guidebooks for the Canadian Rocky and Selkirk Mountains. He is author of “The Great Glacier and Its House” and “Joe Dodge, One New Hampshire Institution.”

NOTE: If you’d like to continue the story, head on over to Bearding the Old Man—Part Two

NOTES

- Putnam, William Lowell. “Bearding the Old Man—Part One.” The Resuscitator (OH Association), Spring 1991, 3–5.

- “Bill Putnum Was Prominent Broadcaster, Alpinist.” Vineyard Gazette, December 23, 2014.

- Bishop, James Gleason. “Meet Joe Dodge.” New Hampshire Magazine, November 1, 2006.

- “Joseph Brooks Dodge Jr.” Old Hutcroo Association, January 17, 2018. Originally published in The Conway Daily Sun.

- Corey David Photography. “Lakes of the Clouds Hut.” Photograph. Appalachian Mountain Club: Lakes of the Clouds Hut. Accessed November 27, 2025.

- “Lonesome Lake Fishing Camp.” Photograph courtesy of the Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society.

- “Lonesome Lake – an 1876 Fishing Camp Built by Author W.C. Prime – Becomes Part of the AMC Hut System.” AMC Timeline of Significant Events. Appalachian Mountain Club. Accessed November 27, 2025.

- Jeffrey Joseph, Old Man of the Mountain on April 26, 2003, Seven Days Before the Collapse, photograph, 2003.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

© 2025 Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society, 501(c)(3) public charity EIN: 22-2694817

Design by The Palm Shop | Customized by Studio Mountainside

Powered by Showit 5

|

Find US ON

Fall 2025/Winter 2026

Visit by Appointment Only:

Please email us at uphsnh@gmail.com

Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society

26 Church Street

PO Box 863

Lincoln, NH 03251

603-745-8159 | uphsnh@gmail.com