Life in Washington

December 31, 2025

By Mrs. Sherman Adams (LIFE Magazine, May 25, 1959)

Our Six Years in Washington’s Whirlpool

Wife of President’s Former Aide Reveals Excitement and Hazards of Capital Life

For six seasons I watched spring, in all its fragrance, arrive in Washington, D.C. Now my husband and I are enjoying the beginning of a more elusive springtime in our village of Lincoln, N.H. After nearly 20 years in public life it is wonderful to be back.

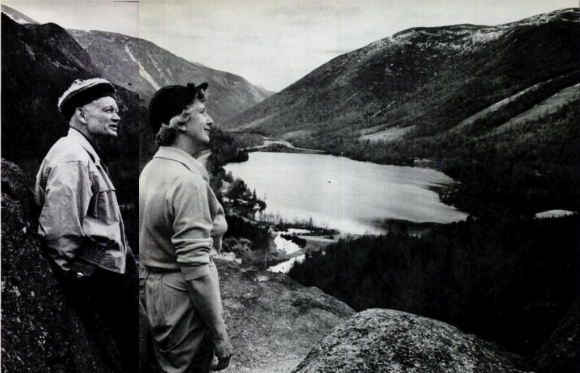

IN NEW HAMPSHIRE, Sherm and Rachel Adams enjoy the view from hill overlooking Echo Lake. Lake is in Franconia Notch region, a skiing-hiking-sightseeing area near the Adams home.

This is the New England where we were born, where we grew up, and where we were first drawn together 37 years ago. Here we have brought up three girls and a boy, and they, like us, appreciate country living. In this past winter our grandchildren were following in our ski and showshoe tracks—and even breaking trail at times.

As we were when the first snow fell, we are now excited about the arrival of spring. Winter lingered with its usual tenacity: the frost went deep and the snow piled high. We are partial to those exhilarating, frosty days and all the good times that go with them, but spring has a fascination too and a promise of the things the coming months have in store for us.

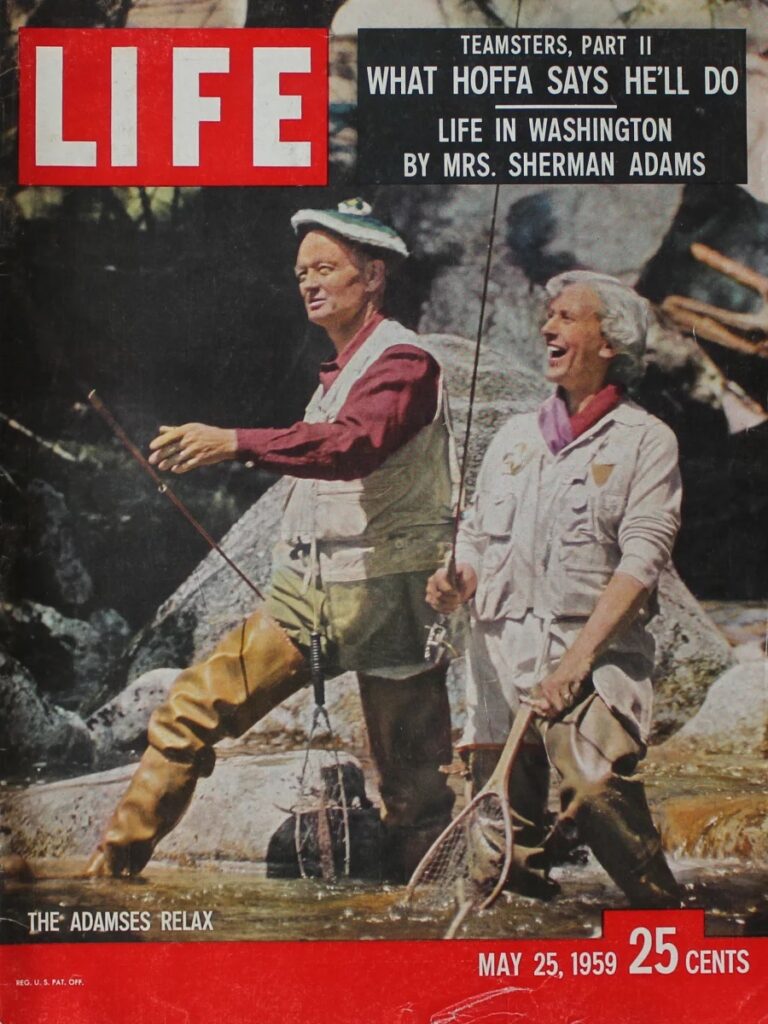

The roar of high water in the river across the field and down over the bank announces that the east branch of the Pemigewasset has finally broken out of the icy grip of winter. Its cold fingers are reaching up onto the slopes of Kancamagus and Whaleback mountains, pulling down the last reluctant pockets of snow. It is time for a close inspection of our favorite trout pools (see cover), and the rods and reels, flies and lures are all in readiness.

We are now a long, long way from Washington. As I look through my window at the tall evergreen spires and the mountains beyond, listening to the music of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto, I say to myself: this is living. And I should never have appreciated what this really means to me and my husband had it not been for the Washington experience. The Washington years were the most strenuous I have ever known. They were the most interesting years, too, for life in Washington has many different aspects, but underneath the thin, superficial covering there are treacherous spots for the careless. Like an icy ski-slope late on a gray January afternoon, Washington is full of unexpected hazards. We met them all, beginning with the 1952 election.

The Governor gets a job

AT INAUGURAL BALL in Washington, when her husband was presidential aide, Rachel Adams stands with Sherman in receiving line to welcome guests at the start of President Eisenhower’s second term.

Maybe Ike would have been elected to the presidency if someone other than my husband had been managing his campaign, but I sincerely doubt it. The Governor (the title he has had ever since he was elected governor of New Hampshire in 1948) had what it took to make the crusade work, and he gave it all he had. Nothing was too hard to try. Nothing was impossible until proven so. The President-elect acknowledged these traits by asking the Governor to be his chief-of-staff in the White House, just about the toughest job a man could have. That is how I happened to leave my New England home and family and take up housekeeping in Washington.

The nation’s capital, with its first change in administration in 20 years, ought to have been a paradise for house-hunters from New Hampshire, for there was a mass exodus of Democrats. But though there was a wide range of real estate available, the prices all centered pretty much around one level, which was high. “Oh, you Republicans,” one realtor said to a friend of ours. “You all insist on living within your incomes!”

The Governor managed to find time for only two or three house-hunting expeditions with me. There was a quick inspection of some real estate which a delightful blonde with an ambrosial accent “just knew” we would like. The blonde went over well with the Governor, but neither of us was interested in the property. The charming old federal place on Capitol Hill, which we eventually rented, wasn’t just what we were looking for but there was no time for more house-hunting. The inauguration was at hand and the need to get settled was urgent.

ARDENT MUSIC LOVERS Governor and Mrs. Adams listen to a symphony on hi-fi set. Painting on back wall is of Daniel Webster, an Adams hero.

Just as the change of administration affected the real estate business, so vibrations were felt in other circles on the Washington scene. Hostesses were busy replacing the old names with new ones. It was astonishing to find how quickly some of those hospitable souls could accommodate themselves to the new political order. Of course, many of those warmhearted women had a preference for Republicans and were overjoyed at the change which was finally taking place. They were intent on making up for lost time.

Washington hostesses soon discovered that some of the new faces in the government were not going to be seen too often at late evening affairs. Most of the men on the Eisenhower team felt as my husband did. They had come to Washington with determination to do a good job, and they thought one of the best ways to accomplish their purpose was to use the nights for rest and preparation for the next day’s duties.

For the first few months of the new Administration I, too, was scheduled to be out of circulation. We had barely settled in the C Street house and got past the hectic excitement of the inauguration when I received a terribly discouraging piece of news. A series of X-rays revealed early tuberculosis. Less than a month after starting our new life in Washington, I entered the hospital. I did not leave for six months. In many ways this was the most trying period of my life. I had never been sickly. I certainly did not feel ill, and I was so disturbed at not being in the thick of things that I never fully accepted the doctor’s decision to keep me in the hospital.

It must have been even harder for my husband, who was starting the most grueling job he had ever had. He thoroughly understood the needs of the new President and he labored at the Assistant’s task from early morning until long after most offices in the capital city had closed. And I, who should have been able to provide him with a restful and orderly home, was now one of his burdens.

The Governor found life on C Street without a wife almost unbearable. Except for his adored Siamese cat, he was alone with his hi-fi and his homework. Each night after stopping at a restaurant for a quick dinner, he would drive several miles to the hospital for a visit. Generally too tired to talk much when he arrived, he would hand me the mail and often a special thoughtful remembrance he had brought along.

“What have they done to you today, Plum?” was his usual question.

If there had been any new medication, I would tell him about it. Then, after a few moments during which I glanced through my mail, he would rise wearily from the chair saying, “Well, guess I’ll go along and get to bed. This has been a hard day, Plum.” And he would leave for an empty house.

In early August I finally left the hospital. The last X-rays showed complete recovery and life suddenly seemed bright indeed after all those dreary months. My first job in Washington after my recovery was to find a house more to our liking. A not-too-large house, offering seclusion and privacy and fitting exactly into our budget, was all we asked. But everything was either too big or too expensive—or both.

One day an agent called, and the information she gave made me want to see the property immediately. Stepping past the gate at the Tilden Street address was like stepping from a busy city into the peace and quiet of a countryside. The old fieldstone house overlooked several acres of lawn, abundantly planted with many different species of trees and shrubs. Walking through the ancient oak door, I immediately noticed a fine portrait of Sir Winston Churchill. Like the house itself, Sir Winston had a friendly and comfortable appearance. I became more excited every minute. As I walked down the two steps from the hall into the living room and glanced around, I said to myself, “This is it, I think!” A peek into the dining room with its large tavern-type table and an immense fireplace made it hard for me to contain myself. Now I knew this was the place we had been waiting for.

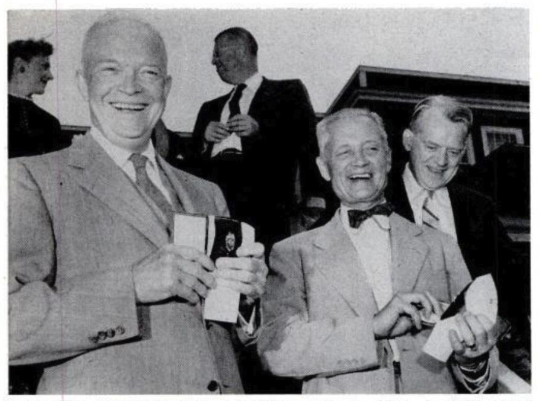

VISITING ADAMSES’ HOME TOWN, Lincoln, N.H., in 1955, President and Sherman Adams display police chief badges presented to them.

It was our type of house: as relaxing as the slow tick-tock of the grandfather’s clock by the living room door, as warm as Sir Winston’s smile in the front hall, as dignified as only hand-hewn timbers and carefully selected stones knew how to be, as secluded as the brown thrasher’s nest in the brambles by the fence. I could hardly wait for the Governor to see it.

Next evening I herded my husband in through the gate, then for a look around the corner of the house. We went inside, went through the hall, then to the living room, then to the dining room. The Governor took in everything on the way but uttered not a word until the charm of the dining room prodded him. Then he said, with noticeable relief, “Plum, I guess you’ve found your house.”

Our new home made the years in Washington much more enjoyable. We had privacy, but it was only a 15-minute drive to the White House. It was in the midst of Washington, yet somehow miles away.

After the all-important hi-fi was properly installed, we adopted a routine. The alarm clock pierced the dark winter mornings at 6:15. While I prepared breakfast, the Governor turned on the Washington good-music station, then went in search of the morning paper. We sat down to breakfast about 10 minutes of 7. Traces of morning light would begin to appear in the sky above the mimosa tree on the hill. As the light increased, so did the flock of crows which were slowly circling above the zoo a mile away, where it was feeding time for the birds and animals.

After a second cup of coffee the Governor would finish reading the paper, then drive to his office, arriving there about 7:30. I would not see him again until dinner time.

Home again in the evening he would immediately turn on the radio if a good-music program was scheduled or else play some of his favorite records. As long as he was in the house there was music. Evenings after dinner were often spent playing Scrabble or rummy.

In spring and summer we would get in a little golf before a late dinner. I found my golf swing had suffered considerably as a result of my sojourn at the hospital. I also worried about losing my ability to cast a fly. We both had a particular fondness for a stream, a rod and a reel. The occasional weekend trips to Little Hunting Creek, up in the Catoctin Mountains of Maryland, were always a pleasant respite after weeks of battling the Washington whirlpool.

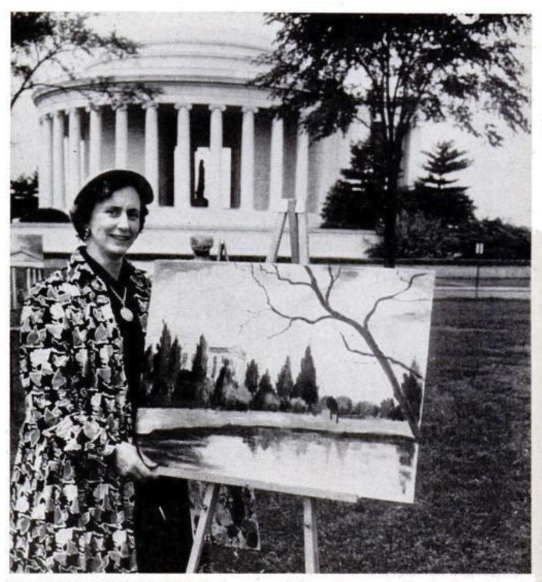

Not having a regular maid, I always had plenty of household duties, but I made time for my special projects. The most fascinating of these was the painting class I joined at the beginning of my Washington stay. That group was made up of busy women who, like myself, found real enjoyment in applying their extra energies to some tangible accomplishment. Often we would forgo luncheons and teas to spend the time sketching on of the lovely Washington landscapes.

THE AUTHOR AS ARTIST shows a painting she made during her stay in Washington of the Jefferson Memorial (rear) and the adjacent tidal basin.

For a few of the government wives, Washington was an unwelcome change. Washington was only a tolerated interim between frequent trips back home. There were still others who refused to make the break from home and came to the city only for very special occasions. But for the most part wives followed their husbands to Washington, determined to try to enjoy the transformation and fully resolved to keep their sense of balance.

Many wives, of course, like myself had had some experience in public life. This helped. Our previous initiation with long lines of handshakers made the occasions in Washington “to stand in line for a little while” a lot easier. Shaking hands is an old New England custom. Campaigns and receptions during many years of public life put me in good condition for serving in the receiving lines. Meeting friendly people and introducing them to the next in line is a pleasant function—provided you wear comfortable shoes!

Protocol is one of the ever-present realities of Washington life. When we arrived in Washington the gentleman who knew most about social pitfalls and how to avoid them was the affable John F. Simmons. For a number of years as the State Department’s chief of protocol he had been responsible for interpreting the rules and dispensing the wisdom in the business of being polite to people, particularly foreign visitors. But even Mr. Simmons was fallible.

In 1953 the President traveled to Canada for an official visit. The Governor was invited to go along because of his considerable knowledge of Canadian affairs and because of his friendship with numerous Canadian officials. I was also invited aboard the special train, and John Simmons went along to look after everybody’s social behavior.

The party had been issued instructions regarding correct attire for all occasions while in Canada. Mr. Simmons suggested the gentlemen appear in short black coats and striped morning trousers for the official welcome in the Ottawa station. We were still some distance from Ottawa when word of a major disaster spread through the train: Mr. Protocol couldn’t find his own striped trousers. Still, he was later most dignified in stripeless pants.

Precedence, which might be described as the privilege of arriving last and departing first, is an integral part of Washington social functions. When we were at a formal party, the ranking guest enjoyed all prerogatives connected with his position unless, as happened on some occasions, my husband decided he had had a long enough day. Then the ranking guest lost his privilege of departing first.

One evening we were invited to dinner at the British Embassy to honor the Queen Mother. After the reception everyone moved into the music room and settled in the rows of chairs for an informal musical program. President and Mrs. Eisenhower sat up front with the Queen Mother and Lady Makins, the British ambassador’s wife. The Governor and I took seats near the back of the room.

The program was filled with old favorites, but the evening was getting on. As additional numbers were asked for, I guessed that my husband was thinking seriously about going home. Sure enough, he nudged me. As unobtrusively as possible we crept out into the hall—and ran straight into the ambassador. The Governor muttered something about its being almost time to get up and go to work and that he was sorry but he would have to be getting home. The ambassador replied very softly, “I say, Governor, I wish I could join you!”

Usually the Governor wasn’t the only one ready to depart. There would be other glances in the direction of the ranking guest—glances which meant, “Don’t you think it is time to go home?” Once or twice when my husband was ranking guest, everyone got to bed early.

The city’s leading hostess was, of course, Mrs. Eisenhower. I shall never forget one invitation she extended especially for some friends of mine. The friends were members of a sewing club in Lincoln, and five of them came down from New Hampshire to visit me. From the time our children had been small we had always met regularly to keep up with current events and dispense with mounds of mending while enjoying each other’s company. When Mrs. Eisenhower heard of my friends’ impending visit, she said, “Rachel, why don’t you bring your group down to the White House for tea?”

The only date still open on the First Lady’s calendar was the 10th of March, the day my friends were arriving. They expected to reach Tilden Street the latter part of the morning, which would give them plenty of time to rest up and be ready for tea with Mrs. Eisenhower. But it was actually 3 o’clock when the weary ladies finally turned into our driveway. With everyone chattering at the same time it was hard for me to make an announcement which needed immediate attention.

“Listen carefully,” I told them as they paused for a moment, gathering up numerous bags, packages and plants. “It is now 3 o’clock. At 4 o’clock Mrs. Eisenhower is expecting you for tea. You have to be ready by 3:30.”

Women never unpacked so fast or forgot their weariness so quickly. Everyone appeared shining and resplendent, complete with white gloves, at precisely 3:30. Little had we imagined in those earlier years, as we lengthened growing girls’ dresses or patched our boys’ overtaxed blue jeans, that we would some day be having tea with a President’s wife in the White House.

Dinner at the White House

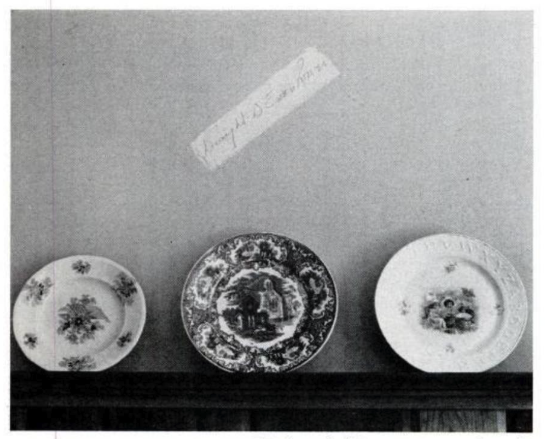

State dinners at the White House were exciting affairs. Entering the dining room, we would find a beautifully decorated E-shaped table. The flower centerpieces were generally in shades of yellow, harmonizing nicely with the soft green paneling and gold upholstered chairs. Then there was the gold flatware, the epergnes and plateau from the Monroe administration, and the green-and-gold china from the Truman regime.

After dinner the gentlemen would leave their ladies at the door to the Red Room and have coffee and liqueurs alone. In the Red Room Mrs. Eisenhower would circulate among her guests, paying special attention to those who had not been included in a White House dinner before. Several times when a queen was present and seated on the small sofa directly beneath the portrait of Abraham Lincoln, the ladies would be introduced and have a few moments to visit with her majesty.

After about half an hour Mrs. Eisenhower would lead the way to the Blue Room where the gentlemen would be waiting. Escorts would find their partners and, with a white-gloved hand on their arm, follow the President and the First Lady into the East Room. The Eisenhowers took their place in the middle of the front row of gold chairs. Cabinet members and other top government officials settled in the rest of the other government officials and friends who had been invited for the musicale. After the program and the departure of the host and hostess, guests were free to depart—in the usual order of precedence.

In June 1955 we got an unusual chance to repay the President for his Washington hospitality. He was making a trip through New England and was scheduled to pass through our home town of Lincoln.

I arrived home a week before the great day and found the whole town busy with preparations for the President’s visit. Several buildings along the main streets were getting new coats of paint. A professional decorator was hanging bunting. Everyone in town received a reminder in the mail or in a pay envelope asking that all lawns be cut by the time the Gentleman from Washington arrived.

Then I had my great idea. There was more time on the President’s schedule than he would need to get to the next town. Why couldn’t he stop at our house for coffee? The idea was tremendously exciting. And practical too. Just when would a President be coming our way again?

Next day I paid a visit to the advance Secret Service detail at the State House in Concord. First, I suggested that they change the proposed route through Lincoln from Maple Street to Church Street in order that the President might see the churches, hotel, schools and library. Then, even before I could bring up the most important part of my plan, the Secret Service men confided that they were very anxious to find a place for the President to stop and relax along the way. The rest was easy. He would stop, of course, at the Adams house.

The Governor, when I called him to announce the change, was not as pliable as the Secret Service had been. It seemed as though everybody in New England had been calling him to ask that the President stop here or stop there, and now his own wife was joining the crowd. He said, very firmly, that he positively did not want to hear about the President stopping ANYWHERE not previously scheduled for ANYTHING, not even for ice cream. I never argue with my husband. I just went ahead with my plan.

The next few days were as busy as any I had ever spent. The house was scrubbed from top to bottom. One man trimmed the lawn and shrubbery; another fixed the loose bricks on the front steps; a third planed down the bottoms of the doors, which always stuck. I dabbed all scratches with fresh paint.

My silver service and tea napkins were in Washington, so I borrowed from neighbors. Homemade doughnuts and cookies were ordered. I made a final trip to the beauty shop to have my hair done but had to wait until the hairdresser had returned from fixing up a dear old lady who had passed on the night before. Then, after a last look around the house, I left for Concord where I was to meet the presidential party. Next day we would all return to Lincoln.

After the speechifying in Concord, the presidential party spent the night in Laconia. The Governor’s first remark when I saw him that day had nothing to do with my plans. He merely asked, “Where did you get that hat?” When I told him that I was expecting the President for coffee, he only asked if everything was under control. I was surprised and very relieved. The Secret Service had obviously given strong support to my invitation.

The motorcade entered Lincoln by the old iron bridge. The President and my husband waved to a group of woodsmen, and we all passed under a sign which read, “Lincoln welcomes IKE and SHERM.” We drove right up Pollard Road. All the neighbors were out. The town sparkled in the fresh morning sunlight. Even the Walshes’ dog was sporting a big red bow.

The motorcade slowed down and stopped at our house. Being as usual on the tag end of the column, I got inside after the President and all the other dignitaries had entered, but I heard later that the President’s first remark was “My, that coffee smells good!”

Everything went perfectly. We all had doughnuts, cookies and coffee. But I suddenly realized that one important thing was missing: my guest book was in the Washington house. I just had to have the President’s signature, so I asked him to write his name on the wall above where he was sitting. The Governor heard us talking and raised his brows. “What’s going on?” he asked. The President grinned. “Your wife and I have a little project in mind,” he replied, and then he autographed our wall.

IKE’S SIGNATURE ON WALL of Adamses’ dining room, put there by President on his visit, was carefully left untouched when room was repainted.

Finally Jim Hagerty suggested that it was time for the President to leave. “Now don’t rush me,” he said. “This is the most relaxing place I’ve found. And I’m going to have another cup of coffee.” When the party finally left the house a few minutes later, it was all I could do to keep from grinning a triumphant I-told-you-so right at the Governor.

That same year the world was shocked by news of the President’s heart attack. In the anxious weeks that followed, my husband was a commuter between Washington and Denver. But the crisis passed; things settled back to hectic normality. The President went on to win another landslide election. As a celebration Christmas present he gave the Governor a beautiful golf bag.

The trouble was that we in the family gave the Governor a golf bag, too, not knowing what the President had in mind. My husband put on a fine show of appreciation as we watched him unwrap our present, and it wasn’t until later in the day that he got up enough nerve to tell us about the duplication. “I feel terrible not keeping yours, Plum,” he said, “but I don’t need two bags.” Naturally we agreed that our golf bag must go back to the store. One just doesn’t go around exchanging gifts received from the President.

As a person raised on heavy New England winters, I was delighted one February day in 1958 when 17 inches of snow surprised Washington. Traffic was completely paralyzed. For three days snow covered the downtown streets. The Potomac was clogged with ice. It was the worst storm in 70 years.

Returning from church on that very white Sunday morning after the storm, we saw two horse-drawn sleighs cross Connecticut Avenue. I decided I would seek a similar conveyance. As usual, the Governor had work to do so he couldn’t accompany me. But I called the wife of a member of the White House staff and she proved eager to go with me.

The horse we got for the job was a well-groomed and well-behaved animal but the sleigh was somewhat decrepit: the basket-like upper section was falling apart. We got hold of a set of bells and were off on a wonderful un-Washington-like tour.

Washington sleigh ride

The ride through downtown Washington was cold and hilarious. Walkers and shovelers and stuck motorists shouted and waved as we drove past. The bells jangled merrily, silenced only at traffic lights. We even considered calling on Mrs. Eisenhower and headed laughingly for the White House. But then we decided, probably wisely, that the guards would have trouble deciding what to do about clearing a horse-drawn vehicle through the gate with two staff wives in control. Still, it was one of the most memorable sleigh rides of my life.

Watching spring arrive in Washington is a rare experience. The blossoms just seem to explode. After a warm night or two in late March or early April, the transformation is like a miracle. But equally as suddenly, all this can disappear without warning. A hard shower with a stiff breeze and the blossoms are scattered over the ground, gone until another year. During these few days of incredible loveliness, the pace of social Washington steps up. Outdoor receptions are planned, and visitors begin to arrive by the thousands.

The Cherry Blossom Festival takes over the city. The lawns in front of the Capitol are alive with groups of high school students having their photographs taken. But Washington is, by no means, just a city of beautiful blossoms, historic landmarks and happy people. There are section full of misery and poverty. Then too, there are many individuals feeding the fires of jealousy and vindictiveness as they seek credit and political notoriety for themselves.

Our own north country can produce storms and blizzards with little if any warning, but in Washington a squall is always brewing on Capitol Hill. One of those squalls blew our way last summer. We decided that if there was going to be a turbulent change in our political climate, we would weather it to the best of our ability. My husband has never been a man to run for shelter in the face of a storm.

As the turbulence increased, I learned a number of things about political attack that I hadn’t known before. One of those lessons was the destruction of the myth that “a man’s home is his castle.” During those days when the Governor was under fire, I had no protection against intrusion, especially by news gatherers and photographers. There were a few members of the press who didn’t seem to enjoy their assignment, for they apparently had little taste for adding to the troubles of my difficult days. But they all tried to get in. Finally I became so alert that I found myself unwilling to let anyone cross my threshold. My cleaning woman was my strongest protector. She looked up from her work one day to see a clergyman standing in the room. “Who let you in here?” she menacingly wanted to know. She did not realize I had returned from an errand and had invited him in.

I attended my first congressional hearing on the day that my husband volunteered his testimony, and it was later on my birthday that the President told the world he believed in Sherman Adams and needed his help. Not long after that we celebrate our 35th wedding anniversary, and in August we attended our son’s wedding. Altogether it was quite a summer. In between gusts from Capitol Hill we endeavored to go about our duties and pleasures with as little interruption as possible.

September came, and the Governor went to Newport to talk with the President. Members of the press kept a vigil in front of our house. A few days earlier when he had mentioned to me that he was considering resigning, I had replied, “O.K., Sherm, but there is something else you are going to do. You are going on television and tell your side of the story.”

The evening he returned from Newport I stayed at the house and watched the TV screen as my husband gave a superb presentation. Then I returned to the kitchen and finished preparing dinner.

During the days that followed, the political weather cleared. We were about to become private citizens once again. To have participated so fully in the Washington scene is a privilege not given to many. My husband is glad he could give of his strength and his talents to help elect a great President. He is also glad he could devote six years to lightening the burdensome routine of the President’s office. I am pleased that I could share in those experiences with him. All the lasting friendships we found in the Washington life, all the good times we had, have come back to the hills with us in memory. We often stand at the top of one of the mountains where the view is broad and distant and look off in the direction of the Washington whirlpool, no longer even on our horizon. We look at each other and smile.

PRIVATE CITIZENS NOW after his 17 years as a state and federal official, Rachel and Sherman Adams enjoy the peace of their New Hampshire home.

NOTES

- Adams, Mrs. Sherman. “Life in Washington.” LIFE, May 25, 1959, 118–132.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

© 2025 Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society, 501(c)(3) public charity EIN: 22-2694817

Design by The Palm Shop | Customized by Studio Mountainside

Powered by Showit 5

|

Find US ON

Fall 2025/Winter 2026

Visit by Appointment Only:

Please email us at uphsnh@gmail.com

Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society

26 Church Street

PO Box 863

Lincoln, NH 03251

603-745-8159 | uphsnh@gmail.com

Wow, what an interesting insight into Mrs Adam’s time and experiences during the Governor’s time serving in Eisenhower’s term in the White House. Especially enjoyable was that even among the pomp and circumstance of the day the down to earth nature of it all came throughout her story.

We completely agree, Charlie! It appears she never lost herself, despite where she landed. And her pride in being from New Hampshire and calling Lincoln home is so strong. We’re so happy you enjoyed reading this as much as we do!