Becoming Woodstock: A Valley’s Long Journey From Fairfield to Peeling to the Town We Know Today

December 1, 2025

By the time you roll over the bridge into Woodstock today—past gas stations, motels, and the steady stream of cars angling for Franconia Notch—it’s hard to imagine that this valley was once an investment on paper more than a place where anyone actually lived. In the mid-18th century, when Royal Governor Benning Wentworth was busily carving New Hampshire’s interior into speculative townships, he granted a 25,000-acre tract along the upper Pemigewasset to a group of proprietors led by Eli Demerrit. On the royal charter it carried the polished, borrowed name of Fairfield. But on the ground, almost nothing happened. The proprietors sent a small committee north to look over their new holding and lay out lots; then, for roughly a quarter of a century, they stayed away. No houses rose, no fields were cleared. The town existed mainly as ink and intention.

Description of Peeling, New Hampshire as printed in Gazetteer of the State of New Hampshire, in Three Parts by Eliphalet Merrill and Phinehas Merrill.

Real settlement began not with that first, absentee group but with another wave of investors from southern New Hampshire in the early 1790s. They bought up most of the original rights, had the land surveyed into 231 hundred-acre lots, and finally started to move families into the valley. Only at that point did the place acquire something like a lived identity, and with it a new name. When the New Hampshire legislature issued a formal charter in 1799, the town became Peeling—a curious echo of an English place name, but also a word that, in local lore, seemed to match the way this township had been peeled away from earlier grants. By 1800, there were just 83 people here, scattered across a landscape that was more granite than loam.

The early settlers tried to do what New Englanders generally did: scratch out small farms. But the Pemigewasset valley here is narrow, the soils thin, the hills abrupt. Farming could keep a family alive, but it rarely produced the “cash crops” that paid taxes or bought tools. What wealth the land did offer came in other forms. Hemlock covered the slopes, and its bark—rich in tannins—fed a handful of tanneries built along a small body of water originally known as Hubbard Pond, soon rechristened Tannery Pond on 19th-century maps. Maple groves offered syrup, boiled down in modest quantities and sold where it could find a market. A first up-and-down sawmill, built by John McLellan sometime between 1806 and 1816 on the outlet of that pond, turned local timber into rough boards. By the time the census-taker arrived in 1840, there were four such water-powered sawmills in town, working only when the flow was high enough to turn their wheels.

Peeling’s original center sat higher on the flank of Mount Cilley than today’s village, a little hill community with a spruce-oil mill, a schoolhouse that taught around forty pupils, and scattered farmsteads connected by rough roads. A post office operated there from 1819 to 1840, evidence that this upland neighborhood imagined itself as a town in its own right. Yet the terrain that made Peeling picturesque also made it precarious. By the mid-19th century, the official center of gravity—and eventually the population—would slide down toward the river, leaving those cellar holes to be swallowed by the White Mountain forest.

The year 1840 marked a turning point. On paper, the community shed its awkward, much-revised identity and accepted yet another new name: Woodstock, after the English town that includes Blenheim Palace, popularized in Walter Scott’s historical novel Woodstock. It was an aspirational choice, with a distinctly Old World polish, and it aligned the little Pemigewasset settlement with a broader mid-19th-century fashion for romantic English place names in the White Mountains. But the timing mattered as much as the name: by the 1840s, the valley’s future would be less about subsistence fields and more about timber and, increasingly, visitors.

That decade brought an outside figure whose influence would ripple through both Woodstock and neighboring Lincoln: Nicholas Norcross, an experienced lumberman from Maine. Norcross and his partners assembled a vast holding—on the order of one hundred thousand acres—in the Lincoln-Woodstock region. Each winter, crews of 150 to 200 men went into the woods, felling spruce and fir across the high country. In spring, when the thaw came and the rivers ran high, the logs were driven down the Pemigewasset, then into the Merrimack, and finally to sawmills in Lowell, Massachusetts. Over time, Norcross and his associates organized themselves as the Merrimack River Lumber Company, one of the great engines of 19th-century industrial logging in New England.

Those river drives, which continued into the 1880s, became a seasonal spectacle and a rough-edged way of life. From the banks, townspeople watched crews of “rivermen” dance across logjams in iron-spiked boots, prodding, prying, and dynamiting snarls loose before the backed-up Pemigewasset could flood its banks. It was dangerous work, romanticized later in books like Robert Pike’s Tall Trees, Tough Men, but to people in Woodstock it was also simply an annual fact: each spring the river filled with timber and men, and every stick represented cash leaving the hills for the mills downriver.

As the forest economy matured, Woodstock’s mix of industries diversified. Tanneries still scraped hides with hemlock bark. Small starch mills and bobbin shops appeared; hardwoods like birch and maple went into the millions of spools needed by the textile mills in Manchester, Nashua, and Lowell. The town’s name might now evoke English parkland, but its daily rhythms were governed by the slap of waterwheels, the smell of wet bark and hides, and the winter echo of axes.

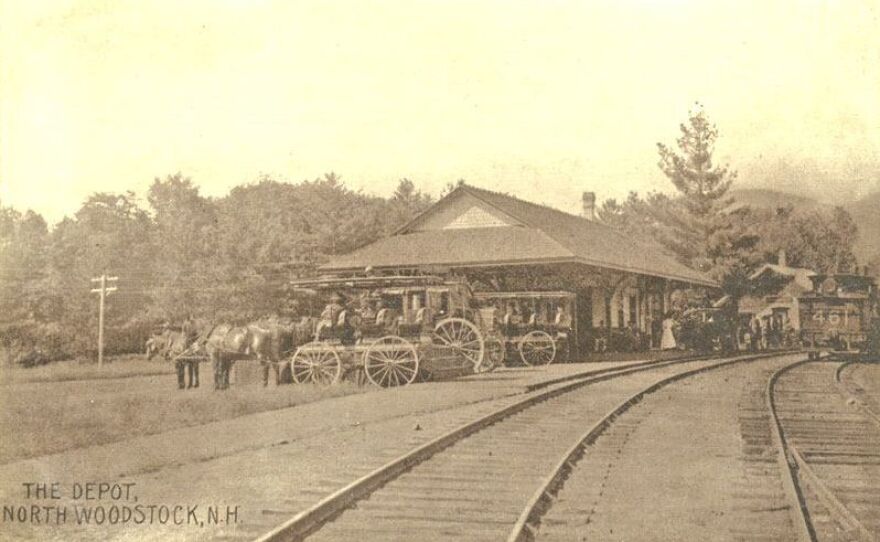

Stagecoach heading from the Fairview Hotel in North Woodstock to the White Mountains

Tourism, too, arrived early, folding Woodstock into the emerging leisure geography of the White Mountains. By the 1870s, stagecoaches met trains at Plymouth and carried summer visitors up the valley to eight or ten local boarding houses. These were not yet the palatial resorts that would later dominate White Mountain postcards, but they were part of the same desire: urban families from Boston, Hartford, New York, and Philadelphia fleeing coal smoke and summer heat for mountain air, carriage rides, and views of Franconia Notch.

The Depot, North Woodstock, New Hampshire

The railroad changed the scale of that movement. When the line was extended to Woodstock in 1883, boardinghouses quickly gave way to substantial hotels. By about 1905, more than 2,500 tourists were arriving each summer by rail, stepping down from Boston & Maine coaches into a village now oriented toward their needs. North Woodstock’s Deer Park Hotel, with its verandas and manicured grounds, became the largest of several hostelries that also included the Mountain View House, the Russell House, the Hotel Alpine, the Cascade, the Fairview, and others. From the station, stages departed not only for those local hotels but for such regional icons as the Profile House in Franconia Notch, which advertised its own mountain views and social scene.

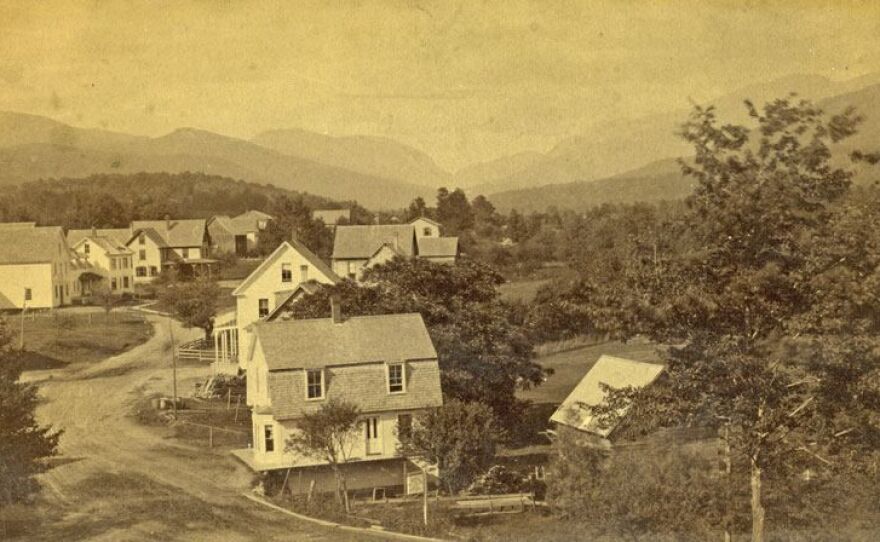

Main Street, Woodstock, New Hampshire (1900)

If tourism gave Woodstock an outward-facing gentility, the early 20th-century logging boom brought an almost industrial intensity to its backcountry. With the arrival of the railroad, floating logs down the Pemigewasset made less economic sense, and logging railroads pushed deep into the hills instead. The Gordon Pond Railroad and the Woodstock & Thornton Gore Railroad linked remote camps with valley mills, hauling out vast quantities of pulpwood and sawlogs. The woodlands themselves belonged, by then, largely to the Publishers Paper Company, which did not cut trees directly but leased operations to contractors like George Johnson—remembered in local accounts as an especially ruthless “wood butcher”—and to large concerns such as the Woodstock Lumber Company.

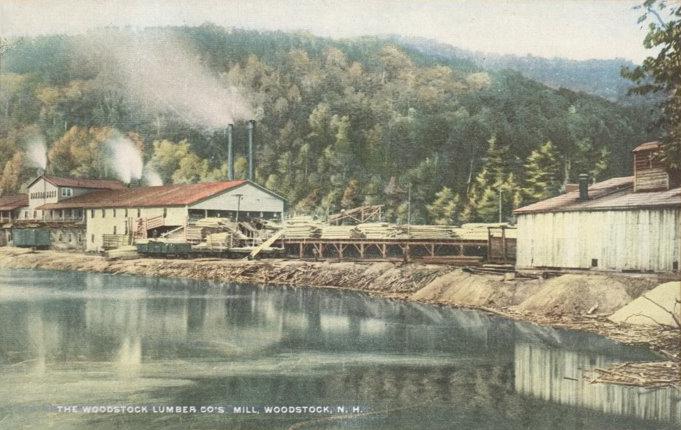

The Woodstock Lumber Company’s Mill, Woodstock, New Hampshire, circa 1915. William L. Hallworth, Malden, Massachusetts.

The Woodstock Lumber Company’s mill, built along the Pemigewasset in 1907, epitomized this industrial phase. It was a steam-powered complex of long sheds, log ponds, and outbuildings, tied by rail to logging camps that spread across the surrounding slopes. Contemporary photographs show piles of sawn lumber stacked almost to the horizon, with the railroad snaking through the yard. For a time, the operation flourished, providing steady wages to men who had once worked only seasonally in the woods.

But the boom carried its own limits. Clear-cutting on steep terrain left slash piles that burned easily and soils that washed into streams. Across the White Mountains, floods, fires, and silt-choked rivers alarmed people downstream. Conservationists, engineers, and local business interests slowly aligned around a new idea: that the federal government should buy up exhausted private timberlands in order to protect watersheds and restore forests. After a long campaign—one in which New Hampshire voices were central—Congress passed the Weeks Act in 1911, authorizing the purchase of forest lands at the headwaters of navigable streams.

In the Woodstock area, federal acquisition began only a few years later. By then, the local timber story had already hit its climax. In 1913, fire tore through the Woodstock Lumber Company’s mill and surrounding buildings, effectively gutting the enterprise; by 1915, the company was defunct. Across the valley, other large operators had cut most of the merchantable timber. A landscape that had once seemed inexhaustibly wooded now presented, in panoramic photographs, a stark pattern of stumps and slash.

Out of that devastation, the modern forest slowly emerged. Federal purchases under the Weeks Act laid the groundwork for what became the White Mountain National Forest, formally established in 1918. As the U.S. Forest Service began to manage these lands, young stands of spruce, fir, and hardwood crept back over the hills. The abandoned hill village of Peeling—its post office closed, its school silent—became another set of cellar holes in a recovering wilderness, now protected rather than exploited.

Walk through Woodstock today and the past layers are all still there, if you know where to look. Main Street, with its general store and restaurants, serves roughly the same function it did when tourists first arrived by train, except that cars now line the curb where carriages once waited. The curve of the Pemigewasset still dictates the town’s geometry, just as it once dictated the course of log drives. A short drive away, condominium developments and vacation homes stand on land that a century ago held mill yards or hotel lawns.

And up the slope of Mount Cilley, under second-growth trees, you can find the faint depressions of old foundations: the former Peeling, a reminder that this town has been renamed, relocated, and repurposed more than once. Fairfield, Peeling, Woodstock—the names sound like successive drafts of a story that the valley has been telling for 250 years. The through-line is not any single industry or institution, but the way the community keeps translating a rugged place into a livable one: first by farming, then by felling trees and tanning hides, then by welcoming summer people off the train, and now by marketing trailheads, breweries, and views. In that sense, the small neighboring town to Lincoln is not just a satellite but a mirror—another Pemigewasset settlement continually renegotiating its relationship to the forest and the wider world.

NOTES

- Merrill, Eliphalet, and Phinehas Merrill. Gazetteer of the State of New Hampshire, in Three Parts. Exeter, NH: C. Norris & Co., 1817.

- Pike, Robert E. Tall Trees, Tough Men. New York: W.W. Norton, 1967.

- U.S. Forest Service. “History of the White Mountain National Forest.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

- U.S. Congress. Weeks Act, 36 Stat. 961 (1911).

- Hurd, D. Hamilton. History of Grafton County, New Hampshire, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches. Philadelphia: J.W. Lewis, 1886.

- Bryant, Thomas. “Railroads and Resort Development in the White Mountains.” New England Railway Historical Review 12, no. 3 (1998): 44–60.

- New England Hotel Register. White Mountains Hotel Directory, 1901–1910.

- Brennan, Edward. “The Deer Park Hotel and the Rise of North Woodstock Tourism.” North Country Historical Journal 5 (1987): 23–34.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

© 2025 Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society, 501(c)(3) public charity EIN: 22-2694817

Design by The Palm Shop | Customized by Studio Mountainside

Powered by Showit 5

|

Find US ON

Fall 2025/Winter 2026

Visit by Appointment Only:

Please email us at uphsnh@gmail.com

Upper Pemigewasset Historical Society

26 Church Street

PO Box 863

Lincoln, NH 03251

603-745-8159 | uphsnh@gmail.com